The purpose of Apramāda is to offer Buddhist perspectives on society and culture. In that spirit, I have been thinking it would be interesting to see what the Buddha himself said about the society and culture in which he lived. There are a few suttas in which he comments on aspects of the society (or, more accurately, the societies) in which he moved. My plan is to examine some of those suttas in this and in future articles.

Before we begin, we should bear in mind that there are a number of difficulties in this venture. Some of these I will highlight as and when they arise, but I will mention one of them here at the outset. We cannot be certain that everything the Buddha is recorded to have said in the ancient texts was really said by him. This uncertainty could give us licence to pick and choose what we believe he said. If we don’t like something because it contradicts our political views, we can just assert that the Buddha could not have said it. Conversely, if something he is supposed to have said conforms to our own political viewpoint, we can accept it wholeheartedly without worrying ourselves too much about its authenticity.

That approach is clearly too lazy for a serious assessment of the Buddha’s statements on society. On what grounds, other than our prejudices, can we judge the authenticity of this or that text? One possible ground for judging authenticity might be consistency: does what the Buddha says in one text cohere with what he says in others? If not, then we can legitimately question it. But even here we have to be very careful. It is quite possible that the Buddha offered particular people teachings that were relevant to their own needs and circumstances, but which were not meant as advice for everyone.

So, how to proceed? My modus operandi has been, in the first instance, to assume that the Buddha did in fact say what he is purported to have said about society in the suttas. And I believe that the Buddha was wise — as wise, in fact, as it is possible to be. So, when I read something with which I don’t agree, I assume, in the first instance, the mistake to be mine, and try to understand his point better. This does not mean that I give up my own critical faculty — just that I am always aware I could be wrong. In the end though, I have to make up my own mind about whether or not I accept what the Buddha said. You, my readers, will no doubt do the same.

In the present article I will examine what is probably the Buddha’s most explicit teaching on the principles that make for a healthy society.

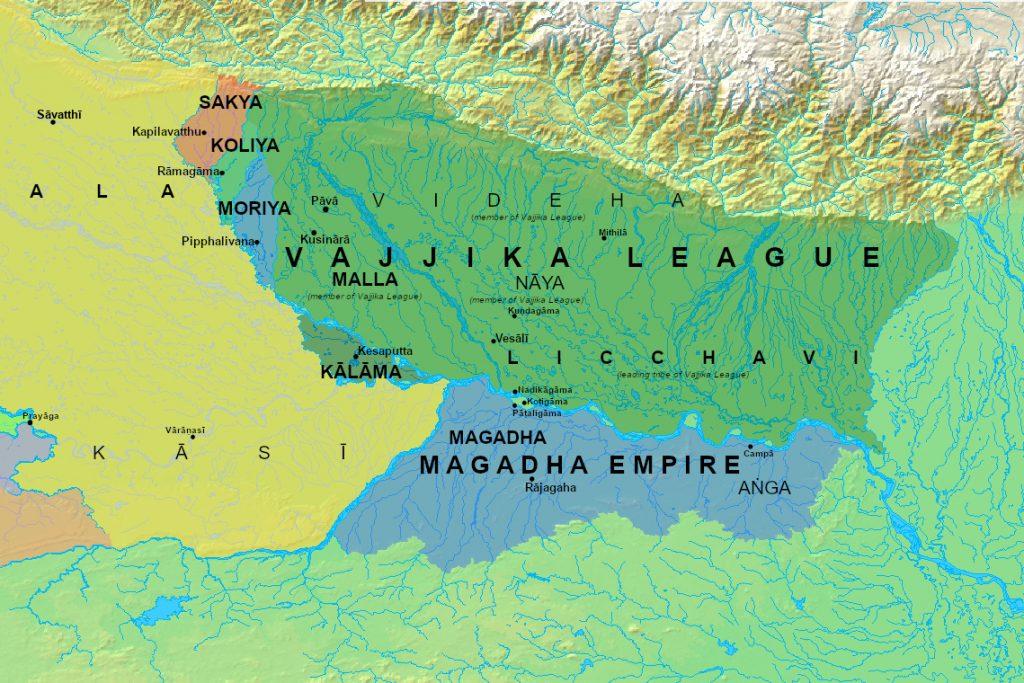

He was once staying just outside Vesālī, the capital city of the Licchavi Republic. This was the leading state of the Vajjika League, a federation of republics (see map above), which was ruled by eighteen representatives from the different member states, nine of whom were Licchavis. According to this sutta the Buddha was visited by ‘several’ Licchavis, and he taught them seven principles that, if followed, would prevent the decline and downfall of the league.1 This is strange. The Buddha was a spiritual teacher, not a political one, and did not usually concern himself with such matters. Why would he, apparently unasked, teach these principles? One possibility is that his visitors had told the Buddha that the league was in decline, and had asked him how they could reverse that trend.

In what follows, I am going to recount those seven principles, and say a little about each. No doubt there is much more that could be said, but I don’t want to overtax my readers with a very long article, and I hope my commentary will provide some food for thought.

- As long as the Vajjis meet frequently and have many meetings, they can expect to prosper, not to decline.

The first of the seven principles emphasises the importance of maintaining good communication between the members of a society. Frequent gatherings, in which people can air their grievances, mediate their differences, tackle certain problems, and facilitate collective action, are an important aspect of any society. The Buddha does not stipulate precisely which members of society he means, but it is probable that he is referring mainly to the leaders of the Vajjian states. These would almost certainly have been from the Kshatriya (warrior or aristocratic) caste and/or the Brahmin (priestly) caste. (There was some variation between Indian states as to which of these two castes was dominant.)

The second principle adds a rider to this:

- As long as they meet in harmony, depart in harmony, and carry on their business in harmony, they can expect to prosper, and not decline.

It is, of course, important for a federation of states to be in concord, as tensions would naturally arise from time to time between the needs of each nation and the needs of the league as a whole. It would also be important for the leaders of each nation to be in harmony with one another, otherwise they would not be able to present a united front in any discussion with the leaders of the other states.

However, there is an obvious danger with this principle: that of ‘groupthink’.

This manifests when the desire for harmony within a group overrides the need to critically evaluate facts and proposals, the result being poor decisions.2 For any group to survive and thrive, its members need to be prepared to disagree with one another — strongly, if necessary.3 So why did the Buddha emphasise harmony, and not balance it with, say, honesty and independence of thought? Perhaps the relations between the leaders of the League had become very acrimonious, a state of affairs which would also prevent, or at least be a hindrance to, their making good decisions. (And perhaps that was why the Buddha taught them these principles).

Modern democratic states have rival political parties, and the party that presently governs is held to account for its performance by the opposition parties. While this is a good system in principle, in practice it often causes the opposition parties to resist every single thing the governing party proposes to do — not because they genuinely think the proposals are bad, but merely because it is the governing party that proposes them. Even if the opposition grudgingly agrees with one of the government’s proposals, it criticises the government for taking too long to act, or for bungling its implementation. This is tedious, and one can’t help but suspect that the opposition is criticising not for the good of the nation, but to gain power.

In addition, the way politicians of different parties speak to, and of, each other is not harmonious, to say the least. In fact they often do so with hatred and contempt. This has become worse in recent years in both America and the UK as both sides — the left and the right — have become more polarised. It should be possible for politicians to disagree and call each other to account while at the same time treating one another with respect. That would not make the political process any less effective. Of course, politicians sometimes do or say things arguably worthy of contempt, yet the contempt is often needlessly personal and venomous.

But let’s return to ancient India and the Vajjika League:

- As long as the Vajjis don’t make new decrees or abolish existing decrees, but undertake and follow the ancient Vajjian traditions as they have been decreed …

The Buddha is recommending here what would now be called traditionalism, or conservatism, which respects and upholds traditional values, morality, norms, and practices of one’s own group or country’ and, moreover, actively resists attempts to change those traditional values etc. Some people would regard this as ‘reactionary’. Yet as we will see, this is not the only conservative principle that the Buddha recommended to the Vajjis.

However, we need to tread carefully here. To use these labels is to project modern political concepts back in time. To say that the Buddha was a traditionalist, a conservative or a reactionary is to suggest that he chose this particular political perspective when he could have chosen others, such as liberal, democrat, left-wing, progressive etc. But such political concepts did not exist at the time. Along with all his contemporaries, the Buddha simply would not have thought in those terms. Which means that if we want to understand the Buddha’s advice to the Vajjis, we have to leave our political ideas aside, and instead try to imagine ourselves in the particular conditions of ancient India. It is not possible to do this completely of course, but it is important to try. Otherwise, we are liable to fall into the trap of judging the past against our modern values.

Still, it is puzzling that the Buddha took this rather extreme position (of advising against changing anything). Did he think that the Vajjika League was the best possible society, and could not be improved? That seems highly unlikely. He is well known for his criticism of the caste system, which would surely have been practised in all of the states within the Vajjika League. Would he not have approved of its abolition? And if so, why did he not say so? However, there are a few things we should take into account before we pass judgement.

Perhaps the Buddha could see that any reforms the Vajjis might make would be subject to the law of unintended consequences. In the specific case of the caste system, for instance, he would have known that attempting to abolish it would have been very unpopular amongst the higher castes, almost certainly leading to violence, perhaps even civil war.

We should also bear in mind that the Buddha was not working with a clean slate. The tribal states that made up the Vajjika League had existed for a long time, and their ways of thinking and behaving were, as the saying goes, as old as the hills. He could not just wade in and expect them to dispense with their ancient traditions, because their cultures were based on them and would have held deep meaning for them.

Then there is the fact that modern nations have to adapt to very changing conditions, and therefore they have to ‘abolish’, or at least adapt, existing laws that are no longer relevant to present realities, and make new ones which are. But the conditions under which nations existed in India 2,500 years ago would not have changed very much from generation to generation, and if a certain law served them well for previous generations, it would serve them well in the present and the future.

Finally, the idea of ‘progress’, which we take for granted, is a modern concept, introduced into Europe, I believe, in the early 19th Century.4 As such it is an idea that would not have occurred to those living before then, and that seems to have included the Buddha.

Given all this, is there anything in this particular principle that would be relevant for today? Perhaps that governments should be careful about changing their institutions, conventions and laws, and do so only after much deliberation. It is easy to imagine that society would be better if we changed certain things, but a government also needs to consider the stability of the country, which is maintained by a certain amount of constancy. Psychologists have discovered what they call an action bias. That is, when faced with a problem, our default, automatic reaction is to act; to do something, even when doing nothing is likely to produce a better outcome.

But let’s move on to the fourth principle:

- As long as they honour, respect, esteem, and venerate Vajjian elders, and think them worth listening to …

Why should the Vajjis respect their elders and consider it worthwhile to listen to them? After all, not all old people are wise. However, in traditional societies such as those in the Vajjika federation, the elders would have had long experience of their community, so would have been repositories of the past — the oral equivalent, we could say, of history books. And you can only learn from the past if you know something about it. Therefore, the elders held a very important place within their society. Again, this too seems to be a conservative principle, based on the view that the flourishing of a society depends more on continuity and on the preservation of the accumulated experience of generations, rather than on ‘progress’.

But the Buddha goes further than simply recommending respect for elders; he also urges the Vajjis to venerate them. In fact some of the adjectives the Buddha uses here can also be translated as worship, devotion and reverence. This suggests that the elders have spiritual as well as practical knowledge. No doubt they would not all have been equally worthy of veneration, but I suppose the Vajjis, like people everywhere and in all times, would have been able to distinguish between those who were truly worthy and those who were not.

Perhaps we should take the Buddha’s advice to signify the importance of listening to the consensus of the elders, rather than to the views of each or any of them. With regard to fundamental moral and social principles, the consensus of the old is likely to be wiser, on the whole, than the consensus of the young.

- As long as the Vajjian men don’t rape or abduct women or girls from their families and force them to live with them …

This would protect women and girls from being treated, by a certain kind of man, as objects rather than as people, which is a good in itself, but how might this prevent the decline and contribute to the prosperity of the Vajjika League? Marriage is an important institution in most traditional societies, and marital exchanges tie societies together, beyond the individual families involved in the marriage. Abducting a girl or woman would inevitably foster disharmony between the families of the abductee and the abductor, and this would tend to undermine the harmony of the whole society.

- As long as they honour, respect, esteem, and venerate the Vajjian shrines, whether inner or outer, not neglecting the proper spirit-offerings that were given and made in the past, they can expect to prosper …

This is interesting, especially as it comes from the Buddha, as it might seem at odds with other things he said. In a verse from the Dhammapada, for instance, he laments that people ‘go for refuge to mountains, forest groves and tree-shrines…’, saying that such places don’t give real security or refuge: only going for refuge to the Three Jewels can give that.5 This, though, is a good example of the Buddha giving different – seemingly contradictory – teachings to different people in different contexts. In the verse from the Dhammapada he was talking about the living of the (Buddhist) spiritual life, the foundation of which is going for refuge to the Three Jewels — an act which only individuals can undertake. But the principles we are now considering were specifically given to a group of nations, to prevent their decline and to ensure their continued prosperity. The distinction between what have been called ‘ethnic’ or ‘nature’ religions, and ‘universal’ religions is relevant here. Ethnic religions are related to a particular ethnic group, and are a defining part of that ethnicity’s culture, language, and customs. Universal religions, on the other hand, are not tied to any particular ethnicity or place, and speak to individuals rather than groups.6

According to the socio-psychologist Jonathan Haidt, ‘there is now a great deal of evidence that religions do in fact help groups to cohere … and win the competition for group-level survival’.7 Among a number of studies he cites one by the anthropologist Richard Sosis, who examined the history of two hundred communes founded in America in the 19th century. Some of these communes were religious while others were secular (mostly socialist). Only six percent of the secular communes were still functioning twenty years after their founding, compared to thirty-nine percent of the religious communes. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn came to the same conclusion through reflecting on his experience in the USSR and, later, the USA:

The strength or weakness of a society depends more on the level of its spiritual life than on its level of industrialisation… If a nation’s spiritual energies have been exhausted it will not be saved from collapse by the most perfect government structure …8

The seventh and final principle is

- As long as the Vajjis organize proper protection, shelter, and security for perfected ones, so that more perfected ones might come to the realm and those already here may live in comfort, they can expect to prosper, and not to decline.

The word translated here as ‘perfected’ is araha, the literal translation of which is ‘worthy’ or ‘deserving’ (of offerings, veneration). Those of the Buddha’s disciples who had attained Enlightenment were called arahants, and the translator, Bhikkhu Sujato (along with other translators), assumes that the Buddha was referring to these. Which he may have been, but it is also possible that he was referring more broadly to all homeless wanderers – practitioners of different religious and philosophical schools – as they passed through the Vajjian states. I tend towards the latter view because, as we have seen from the previous principle, the Buddha did not assume or expect all Vajjis to be Buddhist. In fact, the people of the states in the League could well have had differing religious beliefs and practices. Although the Buddha disagreed with at least some of the teachings of the other main schools of his time, he was also careful not to do anything that might undermine the support they received from their followers. Once, when a lay follower of the Jain teacher Ñātika, converted to the Buddha’s teaching, the Buddha pointed out that his family had up to that time been ‘a well-spring of support for the Jain ascetics’ and that he should consider continuing to give alms to them.9

So, three of the seven principles the Buddha gave to the Vajjika League are religious. It is interesting to note that the cultural anthropologist Richard Shweder, who did most of his field work not very far from where the Vajjika League was situated, identified three clusters of moral themes in traditional societies, which he called Autonomy, Community, and Divinity.10 The ethic of autonomy centres on the self as an individual, and is chiefly concerned with the interests, well-being, and rights of individuals (self or other), and fairness between them. The ethic of community focuses on persons as members of social groups, and includes duty to others, as well as concern with the customs, interests, and welfare of the groups to which they belong. The ethic of divinity considers people as spiritual or religious entities, which means they have a sense of reverence and a duty towards the sacred. The Buddha, it seems, thought that if a nation neglected the spiritual beliefs and practices of its people, it would decline. Or, more positively, a nation could only be called truly prosperous to the extent that it gives due consideration to the spiritual dimension of its people.

The Buddha finishes his advice to the Vajjis by saying:

As long as these seven principles that prevent decline last among the Vajjis, and as long as the Vajjis are seen following them, they can expect growth, not decline.

Why should they be seen to be following them? The answer, I think, is to be found in the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta, which tells us that, a short while before his death, the Buddha was visited by a messenger from Ajātasattu, the king of Magadha (see map above). This messenger had been instructed to tell the Buddha of the king’s plan to invade the Vajjika League, and to report to the king anything the Buddha said in response. Presumably the king was hoping for some kind of prophetic utterance concerning the outcome of his attack. The Buddha did not reply directly. He allowed the messenger to listen to an exchange with his attendant, Ananda, in which the Buddha recapitulated the seven principles, and Ananda confirmed that the Vajjis did indeed live by those principles. After each principle, the Buddha remarked that, as long as the Vajjis continued to observe it, they could expect growth, not decline. The messenger immediately understood the significance of this, exclaiming that the Vajjis therefore could not be defeated, ‘unless by bribery or by sowing dissension’ (literally the ‘breaking of alliance’). Sadly, some while later, Ajātasattu did successfully invade the Vajjis, presumably because he had succeeded in undermining the unity of the League.

Considering the seven principles as a whole we can say that, assuming they are indeed his words, the Buddha was not a social reformer, much less an activist, as some contemporary Buddhists have imagined him to be. In fact on the evidence of this sutta he was a social conservative (bearing in mind the warning I gave above about projecting modern political concepts back in time). His conservatism is expressed unambiguously in the 3rd, 4th and 6th principles: theVajjis should follow their ancient traditions, not changing any of them; they should venerate and listen to the elders; and they should venerate their ancient shrines, continuing to offer the proper spirit-offerings that were given and made in the past.

However, it would be unwise to draw definite conclusions based on just one sutta. After all, it is possible that he didn’t, in fact, give this teaching to the Vajjis (although the fact that he repeats it in another sutta perhaps adds weight to the argument that he did). Rather, we should take into account what he said in other suttas, which may fill out, perhaps modify, our understanding of the Buddha’s thoughts on society, which we will do in forthcoming articles.

Footnotes

- Read the sutta here

- See Irving Janis https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irving_Janis for more on this.

- See Conformity: The Power of Social Influences by Cass R. Sunstein, NYU Press, 2019 and my book review https://apramada.org/articles/conformists-dissenters-and-contrarians.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progress#:~:text=The%20concept%20of%20progress%20was,Enlightenment’s%20philosophies%20of%20history

- Verses 188 – 192 of the Dhammapada.

- This distinction was first made, I believe, by the Dutch Theologian Cornelis Petrus Tiele who, in 1877 cited Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam as universal religions. See also the transcript of Sangharakshita’s lecture Religion: Ethnic and Universal

- Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind, chapter 11, Religion is a Team Sport.

- https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f52c347ae046125e87a148e/t/6073a92fc7789b592ea0489e/1618192687890/Aleksandr+Solzhenitsyn+Quotes.pdf

- Upali Sutta, MN56, 17.

- In the temple town of Bhubaneswar in the state of Orissa, India.