I expect many of you would agree with me when I say that it would have been much better for everyone, the people of Russia included, if President Putin had not given the order to invade Ukraine. But here is a question, perhaps a surprising one: would it have been better for everyone, the people of Ukraine included, if President Zelensky and his ministers had decided not to resist the invaders? There are good reasons why this may have been the better choice. In deciding to fight the Ukrainian leaders knew that, to put it simply, many people would suffer injuries and death, many would lose their homes, and many would be traumatised. And of course, they knew that it was possible that they might be defeated, in which case many people would suffer these things for no appreciable benefit.

In saying this I am not suggesting that they should not have fought the Russians. After all, capitulating to the invasion would also have brought great suffering on the Ukrainian people. Zelensky and his ministers were caught in a cleft stick; whatever they decided to do was bound to lead to terrible suffering.

Here is another question: if a country, ruled by committed and practising Buddhists, were faced with a similar situation, how shouldthey respond? That is, given what the Buddha said about violence and war, what course of action should they take? As a matter of fact, one Buddhist country, Tibet, was in that situation about seventy years ago when China invaded it. I will come to that case presently, but first I want to examine some of the Buddha’s teachings, and consider their implications for war.

The Buddha on Violence

The Buddha was unequivocal on violence. for instance, he said,

All tremble at violence;

life is dear to all.

Putting oneself in the place of another,

one should not kill nor cause another to kill.1

To ‘put oneself in the place of another’ is to imagine what it must be like to be that person. Just as we know that our own life is dear to us, we can assume that other people’s lives are equally dear to them. Putting ourselves in their shoes, it becomes harder, perhaps impossible, for us to kill them. The last line of the verse has a strong bearing on war of course.

The Buddha also said,

“He abused me, he struck me, he overpowered me, he robbed me.” Those who harbour such thoughts do not still their hatred.

“He abused me, he struck me, he overpowered me, he robbed me.” Those who do not harbour such thoughts still their hatred.

Hatred is never appeased by hatred in this world. By non-hatred alone is hatred appeased. This is an eternal truth.2

The Pali word for hatred here is verena, and non-hatred is averena (the prefix ‘a-’ meaning ‘not’ or ‘no’). However, many translators prefer to translate averena as ‘love’ because in Pali a word with a negative prefix means more than just an absence. It implies something positive, rather as the English word ‘immortal’ means more than merely ‘not dead’.

Also, when instructing his monks on one occasion, the Buddha taught them the famous ‘simile of the saw’. He said that, even if a gang of thugs were to use a two-handed saw to cut off their limbs, they should not allow the mind to be adversely affected, but should feel compassion towards their assailants, radiating loving kindness, with no inner hatred. A monk unable to do that, said the Buddha, would not be practising his teaching. This is an uncompromising message.3

The law of karma and rebirth is also relevant to our theme. An unskilful act, motivated by greed, hatred or delusion, will bring suffering on the actor, just as a skilful act, motivated by generosity, love and wise awareness, will result in release from suffering. Harming and killing others, according to the Buddha, is very unskilful, and the results will carry through to one’s future lives. This is an important factor for Buddhists to bear in mind when thinking about war.

The Buddha on War

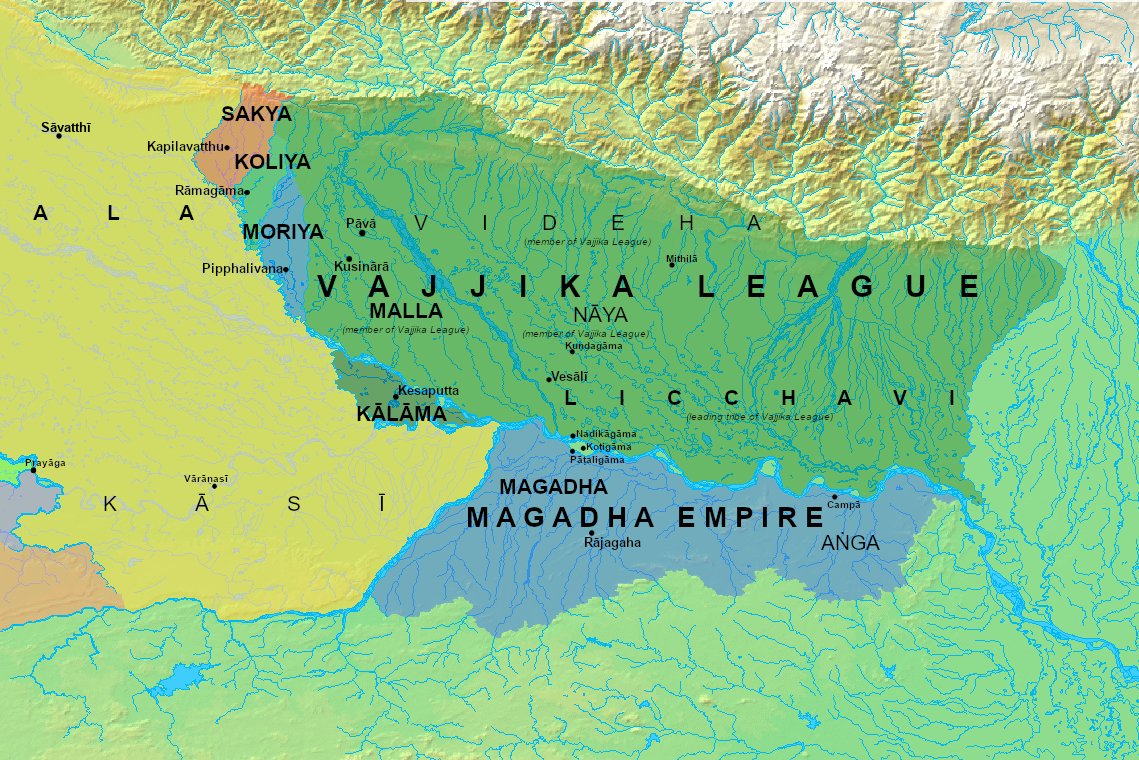

The Buddha counted among his friends two kings, Bimbisara and Pasenadi, both of whom were also his disciples. As kings they had to deal with occasional threats from other hostile rulers. King Pasenadi’s kingdom, Kosala, for instance, was once invaded by King Ajātasattu of Magadha, and was defeated. When the Buddha heard this, he is reported to have said,

Victory begets enmity;

the defeated dwell in pain.

Happily the peaceful live,

discarding both victory and defeat.4

Later though, Pasenadi waged war on Ajātasattu, and this time was victorious. On hearing this the Buddha said,

A killer creates a killer;

a conqueror creates a conqueror;

an abuser creates abuse,

and a bully creates a bully.5

In both of these responses the Buddha makes the point that war is essentially self-defeating. One side may ‘win’, but its victory also sows the seeds for further conflict. The people of the defeated country naturally feel enmity towards the victors and will, if they grow strong enough, return to exact revenge. In this way conflicts can, and often do, continue for a very long time. But notice that Pasenadi went to war even though he must have been aware of the Buddha’s teachings on violence. And notice also that the Buddha did not criticise him for that. He neither condemned nor condoned the keeping of armies, or using those armies to go to war. True, the Buddha did manage to prevent a war on one occasion, and to delay one on another. Most of the time though, war was no more susceptible to his influence than droughts, floods, and earthquakes. He seems to have seen it as something inevitable in human existence — an aspect of samsara, comparable to old age, illness, or any form of physical suffering.

There is another factor to bear in mind. The Buddha had, broadly speaking, two kinds of disciples; lay followers, or householders, and bhikkhus/bikkhunis (often translated as ‘monks’ and ‘nuns’, but really ‘homeless wanderers’). The wanderers lived ‘outside’ of society, so they had no duties towards it. Conversely, society had no claim on them. Specifically, the bhikkhus were not expected to fight in a war, should one occur. This freedom allowed them to practise total non-violence, and the Buddha expected no less of them. As far as I know, the Buddha never gave such an uncompromising teaching as ‘the simile of the saw’ to his householder disciples. He did not blame King Pasenadi for attempting to defend himself and his kingdom against Ajatasattu.6 He understood that lay Buddhists owned property and had dependents, and had a duty to protect them. The bhikkhus, by contrast, only had themselves to protect, and their duty was to ‘abandon what is unwholesome and devote yourselves to wholesome states’.7 In the Buddhas’ dispensation, they had no excuse for resorting to violence, even if attacked.

Violence-Enabling Mechanisms

The fact that the Buddha did not explicitly condemn war meant that he left the door open for later Buddhist leaders to condone and in some cases to encourage and even ‘spiritualise’ it. Brian Daizen Victoria has studied and written extensively on the relationship between Buddhism — or more accurately, Buddhists — and war. For anyone who imagines Buddhist history to be unblemished, Victoria’s findings are disappointing. It seems that although Buddhists are in principle against war, their attitude often changes when their own country is involved. In this connection Daizen Victoria coined the term violence-enabling mechanisms, which he defines as

…numerous malleable religious doctrines and associated praxis that, in certain situations and circumstances, can be reconfigured or transformed into instruments that at least countenance, if not actively condone, the use of violence. These doctrines and praxis are commonly, but not exclusively, activated during times of war.8

To give just one instance, in 1904, when Japan was at war with Russia, D.T. Suzuki, the well-known writer on Zen and Pure Land Buddhism, wrote an article called A Buddhist View of War. In it, he said:

One thing most detestable and un-Buddhistic in war is its personal element. Egotistic hatred for an enemy is what makes a war most deplorable. But every pious Buddhist knows that there is no such irreducible a thing as ego. Therefore, as he steadily moves onward and clears every obstacle in the way, he is doing what has been ordained by a power higher than himself; he is merely instrumental. In him there is no hatred, no anger, no ignorance, no prejudice. He has lost himself in fighting. Resting in this conviction, Buddhists carry the banner of Dharma over the dead and dying until they gain final victory.9

In this short extract Suzuki invokes the Buddha’s teaching of no-self (anatta) and the Shin Buddhist doctrine of Other Power to claim that Japanese soldiers could kill Russian soldiers as a Buddhist practice. This logic leads him to the appalling conclusion of his final sentence.

According to the Buddha, killing or ordering others to kill is akusala, meaning ‘unskilful’; or more emphatically, it is papa, which can be translated as ‘bad’, ‘wrong’, or ‘evil’. But does this amount to an absolute prohibition on Buddhists participating in a war? What if a hostile country attacks your own? Weighing up options, you might decide it is justified to kill others in order to prevent them from killing or oppressing those people you think of as yours. You might think of it as choosing the lesser of two evils. That would at least be more honest than telling yourself that what you are doing is really non-violent, ethical, spiritual, or even compassionate (as has been done).

The Case of the Chinese Invasion of Tibet

At the beginning of this article I asked what a country ruled by committed and practising Buddhists should do if invaded by another country, and I mentioned the case of Tibet as a historical example. The Dalai Lama was both the temporal and spiritual leader of Tibet at the time, so it is interesting to consider what he did and said then.

The Dalai Lama is well known for his advocacy of non-violence. For example, in 2013 he criticised the Buddhist monks who were attacking Muslims in Myanmar, saying,

Buddha always teaches us about forgiveness, tolerance, compassion. If from one corner of your mind, some emotion makes you want to hit, or want to kill, then please remember Buddha’s faith. … All problems must be solved through dialogue, through talk. The use of violence is outdated, and never solves problems.

However, he was not so uncompromising when the Chinese army invaded Tibet. In 1950-51 the CIA armed the Tibetan guerillas to fight them, and in a BBC interview at the time the Dalai Lama said that

It is a basic Buddhist belief that if the motivation is good and the goal is good, then the method, even apparently of a violent kind, is permissible. But then, in our situation, in our case, whether it was practical or not, I think that is a big question.10

Daizen Victoria accuses the Dalai Lama here of using a violence-enabling mechanism to condone war. That is, he used the Buddha’s teaching that ethics is essentially a matter of intention to excuse the killing or otherwise harming of Chinese soldiers. In other words, actions expressive of positive mental states will be ethical, even though they may appear to be unethical. The Dalai Lama’s only doubt was that armed resistance may have been impractical. Presumably, he meant that, given how few the guerillas were in relation to the Chinese army, they had little chance of repelling it. In which case, many Tibetans and Chinese soldiers would have been killed for no practical reason. As the Dalai Lama was aware of this likelihood, it seems legitimate to ask why he did not stop the shipments of arms from America and order the guerillas to stop fighting. But we should not be overly judgemental about this. He was only fifteen years old at the time, and had been suddenly thrown into the leadership of his country amid an invasion.

However, sixty years later he was still of the same opinion. In a congratulatory message that he wrote on the occasion of the UK’s Armed Forces Day of 21 June 2010 he said,

I have always admired those who are prepared to act in the defence of others for their courage and determination… Naturally, there are some times when we need to take what on the surface appears to be harsh or tough action, but if our motivation is good our action is actually non-violent in nature.11

Before going any further, we should look at the Pali and Sanskrit word that is usually translated as non-violence — ahiṃsā.12 It is the opposite of hiṃsā, meaning ‘violence’, ‘harm’, or ‘injury’. The negative prefix ‘a-’, as we noted above, suggests not just an absence but something positive. Thus, though ahiṃsā is literally just ‘non-violence’; it strongly suggests the positive emotions of goodwill and compassion. We should also note that there is an important difference between the word ‘violence’ and the words ‘harm’ and ‘injury’. Violence is an action, while harm and injury are the result of that action. By ‘non-violent in nature’ the Dalai Lama seems to mean a mind, or perhaps we could say a heart, of love and compassion, which he suggests may be present even in the course of actually harming living beings.

The Question of Motivation

Is this really possible? I think it is, but only up to a point. For instance, imagine that you see a young man run up to another and barge into him with such force that they both fall to the ground. That would seem to be a violent, unethical action. However, a split second later you see a large pot of paint crash to the ground, just where the unsuspecting man had been standing. His assailant had just happened to look up at the moment a workman dropped the pot from the 8th floor, and he rushed to save him. It seems fair to say, in accordance with the logic of the Dalai Lama, that the assailant’s motivation was good, so his apparently violent action was actually non-violent in nature. However, the Dalai Lama was referring to war, which is a very different affair from our falling-paint-pot scenario. We must ask whether it is really possible to hit, stab, shoot, or blow up enemy soldiers while they are trying to do the same to you — all the while having a non-violent, loving and compassionate intention? That seems very unlikely.

There is a sutta in which a ‘professional warrior’ tells the Buddha of a tradition that has been passed down by the ancient teaching lineage of professional warriors: if killed in battle, they will be born amongst the devas (divine beings similar to angels). The warrior wants to know whether the Buddha thinks this is true. At first the Buddha refuses to answer the question, but the warrior presses him a second and third time. Eventually the Buddha relents, saying,

When a professional warrior strives & exerts himself in battle, his mind is already seized, debased, & misdirected by the thought: ‘May these beings be struck down or slaughtered or annihilated or destroyed. May they not exist.’ If others then strike him down & slay him while he is thus striving & exerting himself in battle, then with the breakup of the body, after death, he is reborn in the hell called the realm of those slain in battle.13

You may not believe in rebirth or heavens and hells, but what the Buddha is essentially saying is that killing others in battle has a deleterious effect on one’s mind, which will be a cause of suffering for him, whether in a future life or this one (or both).

So, have we found grounds for an absolute prohibition in this story? Again, there is a complication. The term ‘professional warrior’ (yodhājīva) may mean ‘mercenary’. Killing for money is obviously a very unskilful motivation. Would it be different for someone fighting for their country or for some principle, such as freedom? According to the Buddha, the operative factor — what makes killing in a battle so unskilful, and which results in great suffering for the one who kills — is the thought ‘May these beings be struck down or slaughtered or annihilated or destroyed. May they not exist.’ So, the question is whether it is possible to kill others in a battle without this thought.14

In a document called The Law of Armed Conflict, the International Committee of the Red Cross states that in a war troops ‘…are under enormous pressure. Fear, tiredness, frustration, anger, hunger, stress…’ and ‘the need to vent what are natural feelings can lead to thoughts of revenge or retribution.’15 And in an article on the British Library’s website World War One, Matthew Shaw writes,

Despite the famous (but by no means ubiquitous) truces of the first winter of the war, hatred of the enemy — and even the desire to kill — fuelled many soldiers’ ability to keep fighting. Revenge for friends and companions killed, and the experience of being shot at or bombarded, combined with pervasive propaganda and helped to instil national hatred as the war continued.16

Coming to more recent times, Prince Harry, the Duke of Sussex, famously revealed in his autobiography Spare, that he had killed 25 Taliban fighters when he served in the British army in Afghanistan. He said that ‘in the din and confusion of combat’ he saw them as ‘baddies eliminated before they could kill goodies’, and claimed that it is not possible to kill someone ‘if you see them as a person’. The army, he said, had trained him to ‘other’ them, and he consequently saw them as ‘chess pieces to be removed from the board’.17

Going by the above three testimonies, it seems that even combatants fighting for their country, or for a principle or an ideal, will still be behaving very unethically, and will therefore experience great suffering as a result.

The circle Cannot be Squared

Returning to the Dalai Lama’s statements on war that I have quoted above, Daizen Victoria concludes that ‘for the Dalai Lama, the precept forbidding killing is of no concern’. I think that is an unfair judgement. From other things the Dalai Lama has said and written, it is obvious that the principle of non-violence is actually of great concern to him. We should remember that he has always been in an unusual and rather difficult position. He is a Buddhist monk, which, as we have seen, entails the uncompromising practice of non-violence. Yet he is also the ruler of a country, and as such he has to compromise his Buddhist principles, at least where non-violence is concerned. We could say that he has to uphold the duties of both the Buddha and King Pasenadi.

So now let us return to the question I posed at the beginning of this article: if a country led by committed and practising Buddhists were faced with an invasion from a hostile nation, how should those leaders respond? As you will now appreciate, that is a very hard question to answer, and if you were hoping for a categorical answer in this essay, I must now disappoint you.

I interpret the Dalai Lama’s comments as attempts to solve what is in fact an insoluble problem. If Buddhist leaders decide to fight, they renounce, even betray, their principle of non-violence. But if they choose to refrain from violence, they renege on their duty to protect their citizens. And as we have seen, there is an additional factor for Buddhist rulers to take into account — their belief that killing others is very bad karma, which will result in their soldiers’ later suffering, not only in this life but also the next. And thus, the endless round of suffering will go on. It is a circle that cannot be squared.

The Mission

Sometimes, works of art can help us to ponder moral questions that are resistant to reasoned debate. They may not yield a simple answer, but they sometimes shine a light into the depths of the question. Reflecting on the question posed by this essay, I find myself thinking of the film The Mission, made in 1986 and written by the playwright and screenwriter Robert Bolt.18

The story is set in the 1750s, in the Argentinian/Paraguayan jungle. A Spanish Jesuit priest named Father Gabriel sets up a mission station for the Guarani natives. The other main character is Rodrigo Mendoza, who earns his living kidnapping natives, such as those from the Guaraní tribe, and selling them as slaves to nearby plantations. One day he discovers his fiancée in bed with his half-brother, and he kills him in a fight. Mendoza is then so overwhelmed with guilt that he languishes at home, unable to motivate himself to do anything. Father Gabriel visits him and tells him that the only way forward is to undertake a suitable penance. Mendoza agrees and accompanies Father Gabriel and others on their return journey to the mission station. His penance is to drag through the jungle a very heavy bundle containing his weapons and armour — an agonising task that entails traversing rapids and climbing a steep cliff. On their arrival at the mission station, the chief of the Guarani tribe forgives Mendoza for his previous slaving activities, and orders someone to cut away the heavy bundle and toss it down the ravine and into the rapids.19 Mendoza later takes vows and becomes a Jesuit under Father Gabriel.

The mission station is situated in a part of the jungle that belongs to Spain. Under Spanish law, Jesuit missions are protected. However, a new treaty is agreed between Portugal and Spain, under which the Guarani territory is given to the Portuguese, and the Portuguese allow slavery. Father Gabriel is told by his superior that he will have to move the mission to Spanish territory, or the Guarani will be enslaved. But the Guarani refuse to leave their homeland, and Father Gabriel and Mendoza decide to stay with them, though they know that a Portuguese battalion will arrive sooner or later. Mendoza wants to fight the invaders, but Father Gabriel refuses to countenance this because he believes violence is a crime against God. Mendoza decides to break his vows. Against Father Gabriel’s wishes, he recovers his weapons and armour from the river, and trains some of the Guarani in warfare.

When a Portuguese force arrives, Mendoza and his Guaraní fighters engage it in battle. Meanwhile Father Gabriel and his congregation walk calmly towards the Portuguese, singing a hymn. Mendoza is shot and fatally wounded, but just before he dies, he lifts his head to see that the soldiers are also shooting at Father Gabriel and the Guarani who follow him, many of whom are children. They continue to walk and sing as they are mown down.20

Two different men; two ways to meet violence. Which one is right? If Mendoza and his fighters had not met the Portuguese with violence, perhaps no blood would have been shed. The Portuguese soldiers would either have forcibly evicted them from their land or enslaved them, or both. In the event they killed everyone apart from a handful of children who managed to escape into the jungle. I have asked which of the two choices is the right one, but the conundrum doesn’t have a ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ answer. Neither outcome is a good one. A better question is, which one would you choose?

Footnotes

- Dhammapada, verse 130. Translation Buddharakkhita.

- Dhammapada verses 3-5. Translation Buddharakkhita.

- Kakacupanna Sutta, MN 21, v.20

- Sangama Sutta (1), SN 3.14

- Sangama Sutta (2) SN 3.15.

- I haven’t read all of the Pali Canon, so it’s possible that the Buddha did give such an uncompromising teaching to lay followers. If any reader does know one, please let me know.

- Kakacupanna Sutta, MN 21, v.8

- Does Buddhism Hold the Instincts for War? — Buddhistdoor Global

- http://www.thezensite.com/ZenEssays/CriticalZen/A-Buddhist-View-of-War.html

- Does Buddhism Hold the Instincts for War? — Buddhistdoor Global I haven’t been able to find the interview on You Tube that Daizen Victoria cites, so I’m assuming that he is telling the truth.

- To read the whole message, go to http://buddhistmilitarysangha.blogspot.com/2010/06/dalai-lamas-message-to-armed-forces.html

- Pali is the language in which the Buddha’s teachings have come down to us in the Sutta Pitaka. They were also recorded in Sanskrit, and before they were lost were translated into Chinese, and these have in turn been translated into English.

- https://www.dhammatalks.org/suttas/SN/SN42_3.html (The Professional Warrior) Yodhājīva Sutta (SN 42:3) To Yodhājīva

- ‘Thought’ is cetana, which is active thought, intention, purpose, motivation.

- The Law of Armed Conflict, Lesson 3, Conduct of operations, Part A. https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/law3_final.pdf

- How did soldiers cope with war? | The British Library (bl.uk)

- Other veterans of the war in Afghanistan dispute this characterisation of British army training, notably Colonel Richard Kemp, a former commander of British forces in Afghanistan. He says ‘Harry’s description of how British soldiers are conditioned for combat is the opposite of the truth. They are trained to give enemy dead a decent burial, to handle prisoners humanely and to treat the wounded as they would treat their own. The idea that soldiers are trained to see the enemy as chess pieces to be swiped off the board is wrong …it’s not how we trained people’. https://richard-kemp.com/prince-harry-on-afghanistan/

- The film is based on events surrounding the Treaty of Madrid in 1750, in which Spain ceded part of Jesuit Paraguay to Portugal. The story is taken from the book The Lost Cities of Paraguay by Father C. J. McNaspy, and Father Gabriel’s character is loosely based on the life of Paraguayan saint and Jesuit Roque Gonzalez de Santa Cruz. But the film is a drama and departs significantly from the historical facts.

- To watch this very powerful and moving episode go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ui91q7Y9xPk&t=170s Buddhists may be reminded here of the story of the serial killer Angulimala who, on meeting the Buddha, threw his weapons to the ground, symbolising his conversion from violence to non-violence.

- To watch this scene go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GgmGnUzhlfg