In my previous article in this series I looked at a sutta in which the Buddha spoke of seven principles that, if followed, would prevent the decline and promote the prosperity of the Vajjika league. In this article I look at another sutta, in which the Buddha tells a parable about a legendary wheel-turning king. This parable has its origins in the ancient Vedic tradition, according to which a Great Man (Mahapurusa) is destined to become either an enlightened leader of a religion, or a wheel-turning king.

The parable describes a utopia, that is, ‘an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members’. It also describes its decline and fall, and the reasons for this. The Buddha adapted this myth for his own purpose and, according to the translator Bhikkhu Sujato, ‘divested it of all coarse and violent elements’, and instead has the king rule ‘without rod or sword’.1

The wheel is, of course, a prominent symbol of the Dharma, or teaching of the Buddha, as exemplified in the title of his first discourse after his enlightenment, The First Turning of the Wheel of the Dhamma. However, the wheel in this parable (in which it is called the ‘wheel-treasure’) doesn’t symbolise the way to enlightenment, but the way to a just and flourishing society.

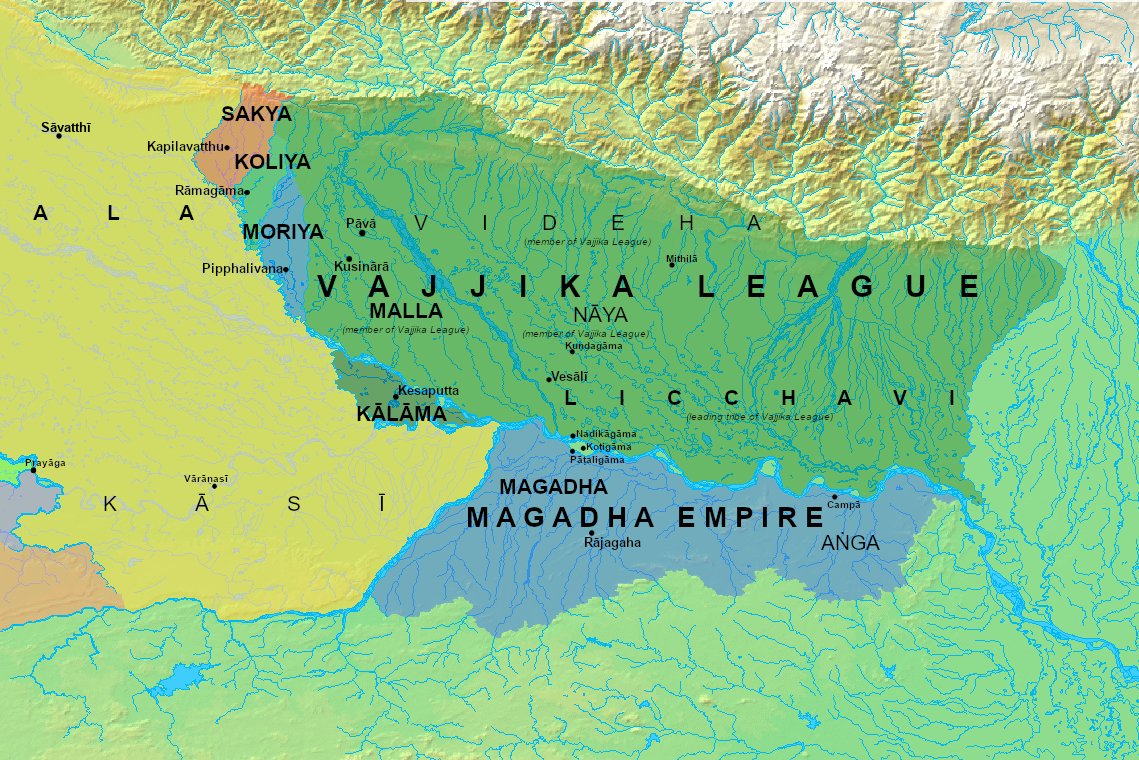

We might ask why the Buddha chose to talk about a kingdom rather than a republic. (He, in fact, came from Sakya, which was a republic – hence one of his epithets is Sakyamuni, ‘the Sakyan sage’). The answer could simply be that he used and adapted the Vedic myth to talk about rulers in general. Or it could be because kings were at that time expanding their kingdoms and the Buddha could see where this was going. As we saw in my previous article, some time after the Buddha’s death King Ajātasattu of Magadha successfully invaded and defeated the Vajjika League of republics. Eventually all the republics were swallowed up, including Sakya, and Magadha became an empire that included vast swathes of what we now call India.

We might also ask why the Buddha decided to talk about a wheel-turning king at all. Did he hope kings would listen to his exposition and change their ways? If so, he went about it in a very indirect way. There are two suttas in which the Buddha talks about wheel-turning kings. In one of them he speaks to his close friend and attendant Ananda, while in the other, he addresses himself to an unknown number of bhikkhus – his disciples who were, like him, homeless ascetics. However, in the latter case he was in Magadha when he told the story, possibly hoping it would eventually reach the king’s ears.

In this respect, it is perhaps significant that the advice he gave to the Vajjika league was not given directly to its rulers either, but to ‘several Licchavis’ – citizens of the leading republic of the league. Perhaps the Buddha made it a rule never to speak directly to kings or other rulers about governance. This could be because his overriding purpose was to teach and encourage people to practise the Dharma, and that purpose could have been compromised had he involved himself in politics. I think that is why, according to the myth, the Great Man becomes either an enlightened leader of a religion, or a wheel-turning king – he cannot be both. A king, even a wheel-turning one, has to use force to protect his country from hostile rulers, and his subjects from criminals, whereas the Buddha was entirely non-violent.

As I stated above, there are two suttas in which the Buddha describes how a wheel-turning king rules his kingdom, but I will confine myself to just one of them – the Cakkavatti Sutta, or the Discourse on the Turning of the Wheel. I mostly use Bhikkhu Sujato’s translation and will also include some of his helpful comments.2

The parable takes place in a land that in many respects is similar to that in which the Buddha lived, although it also includes some supernatural elements. For instance, the population’s average age is 80,000 years, and the king has over 1,000 sons. Nothing is said about daughters, but then the Buddha only mentions his sons in the context of the king’s wars, in which they fought, so it is possible he also had 1,000 daughters too. The wheel-treasure is also supernatural, as we will see.

Once Upon a Time There Lived a King…

The Buddha begins his tale by introducing Daḷhanemi, a wheel-turning king, who was ‘just and principled’.

He had over a thousand sons who were valiant and heroic, crushing the armies of his enemies. After conquering this land surrounded by sea, he reigned by the Dharma, without rod or sword.

There seems to be a contradiction here; although the king rules his empire without violence, his sons have ‘crushed his enemies’ armies’ to achieve it. Could the king only rule non-violently once he has defeated all other countries in battle? This is a disturbing possibility, suggesting that the end justifies the means. However, this could simply be part of the Vedic myth that the Buddha hadn’t adapted.

The wheel-treasure is lodged in a certain part of the palace, and, after many thousands of years it slips from its place, signifying that Daḷhanemi doesn’t have much longer to live. He thus decides to abdicate the throne and leaves the palace to become a homeless ascetic, remarking that he has enjoyed human pleasures and now it is time for him to seek heavenly pleasures. I think this is significant. His spiritual aspiration is to experience the bliss and beauty of the gods, not to gain transcendental wisdom. The king is essentially worldly.

The Duties of a Wheel-Turning King

A week later the wheel-treasure vanishes, which upsets the newly anointed king, Daḷhanemi’s eldest son (whose name the Buddha doesn’t disclose), and he summons the royal sage for advice. The sage tells him that he needn’t feel unhappy, for the wheel was not an inheritance from his father, and it will reappear if he carries out the duties of a wheel-turning king. In other words, he must earn it. The king then asks what these duties are. The sage replies:

Relying only on the Dhamma… having the Dhamma as your flag, banner, and authority – provide just protection and security for your court, troops, aristocrats, vassals, brahmins and householders, people of town and country, ascetics3 and brahmins, beasts and birds. Do not let injustice prevail in the realm. Provide money to the penniless in the realm.

The ‘Dhamma’ here does not mean the Buddha’s teaching of the way to enlightenment; it means, in this context, ‘right, appropriate conduct; duty; what is right; law, justice’. This short statement sums up how, according to the Buddha, an ideal king would rule, and it consists solely of morality. Regarding the last precept – providing money to the penniless in the realm – Sujato says that the word he translates as ‘provide’ is ‘more about fulfilling a moral obligation of fairness than offering charity.’

But there is another duty the royal sage explains to him. The king should occasionally visit spiritual teachers and request instruction on how he should behave, and ‘having heard them, you should reject what is unskillful and undertake and follow what is skillful. This is the noble duty of a wheel-turning monarch.’ There are two important things to note here: firstly, the instruction he should request concerns only ethical conduct, not any further spiritual teachings; and secondly, he should approach teachers from different spiritual traditions (sramanas, or homeless ascetics, and brahmins). Wheel-turning kings are not necessarily Buddhist, and they don’t appear to take up any spiritual practices apart from that of ethics (until they abdicate the throne towards the end of their life, as we have seen).

The king undertakes to perform these duties and the wheel-treasure duly reappears in its usual place. Then, at the request of the king, it rolls to the east; the king follows it with his army and

… opposing rulers of the eastern quarter came to him and said, ‘Come, great king! Welcome, great king! We are yours, great king, instruct us.’ The king said to them, ‘Do not kill living creatures. Do not steal. Do not commit sexual misconduct. Do not lie. Do not drink alcohol. Tax the people in moderation.’4 And those who had opposed him in the eastern region became his followers.5

Once again the king’s admonition concerns ethics; in this case, the other rulers should be ethical themselves. There seems to be a discrepancy in the story here though; Daḷhanemi, father of this king, had already conquered all of these lands, so why would the new king have to do so again? I think the answer is that the new king doesn’t conquer these lands by violence, but by reasserting the principle on which his empire rests: ethics.

He did, though, travel with his army, and the rulers of these countries are described not only as ‘opposing’ (paṭirājāno) but also (although Sujato doesn’t translate this word) enemies (disāya). And yet the king’s message to these rulers is a non-violent one; ‘Do not kill living creatures’. Was the king prepared to use his army if these rulers did not comply? Not necessarily. Perhaps he only did so to protect himself from any possible attack from a hostile force, not because he was prepared to invade any country that did not agree to do as he recommended (or perhaps ordered). What would the king have done if one or more of the ‘opposing’ rulers had not complied? We don’t know, and it appears that the Buddha didn’t think it worth considering that question.

The Decline of the Kingdom

The story then moves on to the (far distant) future. After many thousands of years the wheel-treasure slips from its place in the palace once more, indicating that the king will die shortly. Like his father before him, he abdicates and leaves the palace to become a homeless ascetic, and a new king is consecrated. This king undertakes to fulfil the duties of a wheel-turning king and so becomes one, just like his father. This sequence of events occurs repeatedly over hundreds of thousands of years until it reaches the seventh king in the lineage, who doesn’t ask the royal sage about the duties of a wheel-turning king, but instead rules ‘according to his own ideas.’ As a result, the empire no longer prospers as it did under the previous kings. His ministers, counsellors, professional advisers and others therefore gather to address the king. They inform him that the kingdom is in decline, and that he should take up the duties of a wheel-turning king to reverse this process. He decides to fulfil all except one: he does not provide money to the penniless in the realm. There then follows a sequence of events that leads to the decline and fall of the empire.

Because the king doesn’t provide for the very poor, poverty becomes widespread. Out of desperation, a man steals from another. He is arrested and taken to the king. The king asks whether the charge brought against him is true and he admits it is. The king then asks him why he did so. The thief replies that he stole because he had nothing to live on. The king understands and empathises with the man’s plight, pardons him, and gives him money, saying

With this money, mister, keep yourself alive, and provide for your mother and father, wife and children. Work for a living, and establish an uplifting religious donation for ascetics and brahmins that’s conducive to heaven, ripens in happiness, and leads to heaven.

In the previous article in this series I referred to the cultural anthropologist Richard Schweder, who discovered there are three fields of ethics in traditional societies: autonomy, community and divinity.6 Each of these is represented in the king’s admonishment.

Later, another man is arrested and brought to the king on the charge of stealing, and once again the thief tells the king that he did so because he has nothing to live on, and again the king gives him money. However, this created a new problem. Once it was known that the king was giving money to thieves rather than punishing them, others began to steal in the hope that they too would be caught and that the king would give them money. But after some time the king realises that theft will increase if he gives money to every thief. So the next time someone was brought to the king on the charge of theft, he has the unfortunate man beheaded.

With this action the king breaks the first precept – ‘Do not kill living beings’ – which leads to a cascade of unintended consequences. Following his example, some people make swords and not only steal from others, but kill them too. Before long violence becomes widespread, and as a result of that, the lifespan and beauty of the population declines. Sujato makes two perceptive comments here. Firstly ‘the violence of the state leads to an armed and violent citizenry’ and secondly, ‘we can see, even among developed nations, a degraded and violent culture leads to declining lifespans’.

But why should their beauty decline? Here we must remember that this is a parable, so we should ask what their beauty signifies, and why are they losing it? The Buddha considered ethical actions to be beautiful, and while someone may be physically beautiful, they may be morally ugly.7 Indeed, towards the end of this sutta, once he has finished telling the parable, the Buddha says that ‘beauty for a monk’ is his unblemished ethical practice. The people of this land lose their beauty because of their unethical behaviour.

The king’s new policy being known, the next time a thief is captured and brought to him, he lies when asked whether the charge against him is true. Thus, as a consequence of violence, lying becomes widespread. The kingdom is now on a vicious downward spiral – one unethical action leading inexorably to another – and ends in complete social collapse.

And so, monks, from not providing money to the penniless, all these things became widespread—poverty, theft, swords, killing, lying, malicious speech, sexual misconduct, harsh speech and talking nonsense, desire and ill will, wrong view, illicit desire, immoral greed, wrong custom, and lack of due respect for mother and father, ascetics and brahmins, and failure to honour the elders in the family.8

This downward spiral reaches its nadir in a terrifying vision of an amoral and bestial dystopia:

… anyone who disrespects mother and father, ascetics and brahmins, and fails to honour the elders in the family will be venerated and praised, just as the opposite is venerated and praised today.

There’ll be no recognition of the status of mother, aunts, or wives and partners of teachers and respected people. The world will become dissolute, like goats and sheep, chickens and pigs, and dogs and jackals.

They’ll be full of hostility towards each other, with acute ill will, malevolence, and thoughts of murder. Even a mother will feel like this for her child, and the child for its mother, father for child, child for father, brother for sister, and sister for brother. They’ll be just like a deer hunter when he sees a deer—full of hostility, ill will, malevolence, and thoughts of killing.

A description of a society not too far removed from that of France and Russia in the wake of their respective revolutions, and the ‘cultural revolution’ in Mao’s China.

All this the consequence of the king’s failure to provide for the homeless and destitute. We could say from a lack of compassion, although Sujato makes the point that giving to the poor is ‘not merely a matter of kindness and common decency, but is crucial to ensure stability and national unity.’ Providing for the poor then is not just compassionate but also wise. The king did of course give money to the first thieves who were arrested, but he did so only after they had stolen. And it was arguably his fault that they stole in the first place, by failing to provide for the poor. The parable’s message is that kings (and by extension all kinds of rulers and governments) have a duty to the poor and should not withhold that duty until the poor are so desperate that they have no other option than to steal what they need.

Returning to the point I made above, that in executing the thief the king broke the first Buddhist precept, failing to provide the poor with what they need to live, we could say that he also broke the first precept, by omission rather than commission. The first precept being the foundation of all the others, when that is broken what follows is the gradual erosion of ethical behaviour, from the king right down to the pauper.

Returning to the parable, when the kingdom hits rock bottom the average age of the populace is 10 years. There then follows a ‘sword period’ lasting a week, in which they see one another as beasts, and they kill one another, crying ‘It’s a beast! It’s a beast’. As Sujato comments, ‘dehumanisation of the other is an essential precursor to genocide’.

The Long Way Back

However, not everyone is swept up in this madness. Some, not wanting to kill or be killed, hide in the countryside. At the end of the seven days they emerge from their hiding places and meet others who, like them, have hidden, and they greet one another, saying ‘Thank heavens, dear friends, you live!’ The Buddha doesn’t say anything about those who engaged in the killing, which perhaps means they are all now dead. The survivors realise that it was because of their previous unethical behaviour that they lost so many relatives, and they decide to start practising ethics. They begin with the first Buddhist precept, to abstain from killing living beings, and as a result of this the average age of the population doubles and their children are more beautiful than their parents. Encouraged by this, they extend their ethical practice to include all ten Buddhist precepts, that is, as well as abstaining from killing living beings, they abstain from theft, sexual misconduct, false, harsh, frivolous, and slanderous speech, covetousness, hatred, and false views. The result is that, over many generations, their lifespan increases until it reaches 80,000 once again, everyone is (morally) beautiful, and the kingdom is restored to its former glory.

Significantly, the restoration of the kingdom starts not with the king, but with ordinary people deciding to practise ethics. It is also notable that their decision is not politically motivated. They don’t say that they will be ethical so that the country will become just and prosperous once more. They are motivated by remorse at the loss of their relatives. The parable’s message here seems to be that if individuals are ethical, the society in which they exist will become so too, naturally leading to a just and prosperous nation. Notice too that they don’t blame others for the situation in which they find themselves. Instead they admit that they co-created the society in which they live. The restoration of the kingdom comes about when people begin to take responsibility for themselves.

Eventually, after many hundreds of thousands of years, a wheel-turning king arises once again, completing the long process of regeneration. But then a number of things occur which are new and unprecedented in the parable. Firstly a Buddha, named Mettaya (the Friendly One, more commonly known in his Sanskrit form Maitreya), arises and teaches the Dharma, just as Sakyamuni did, and a sangha (spiritual community) gathers around him. A just and ethically based nation provides the optimum conditions for a Buddha, and therefore the living of the spiritual life, and consequently for a sangha, to be possible. As Urgyen Sangharakshita has said, a positive group (in this case a nation) provides the best conditions for a spiritual community to arise.

As with the wheel-turning kings of the past, when the king realises he hasn’t got much longer to live he abdicates and leaves the palace to become a homeless wanderer. But not so as to be reborn as a god, enjoying the beauty and pleasure of the heavenly realms, but to practise the Dharma under the Buddha Mettaya. Before he dies he attains enlightenment.

Conclusion

The Buddha once spoke of two ‘bright qualities’ which, he said, were ‘guardians of the world (or population)’. These are hiri, conscience, and ottappa, fear of doing anything that will result in suffering to ourselves or others.9 The parable we have been considering spells out why he referred to them as guardians of the world. No matter what the system of government, if the rulers and the people they rule are unethical, the country will fail, bringing terrible suffering to everyone.

At the end of my previous article I said that, on the evidence of the Sārandada Sutta, the Buddha was not a social reformer, much less an activist, but was what we would now call a social conservative. However, I also warned that we shouldn’t jump to definite conclusions based on just one sutta. So now that we’ve examined the Cakkavati Sutta in some detail we can ask, does the Buddha say anything that would cause me to revise that tentative conclusion? No he doesn’t. Even if we assume that he wanted kings to hear his parable and act on it, merely stating how he would like kings to rule doesn’t make him a social reformer or activist.

Notwithstanding this, Gil Fronsdal, an American Buddhist teacher, writer and scholar, has another perspective. In an article called The Buddha as an Activist he says that, while it would not have been possible for the Buddha to have been an activist in the contemporary meaning of the word, nevertheless he was an activist in that he ‘focused on changing how people treat each other.’ Specifically, he taught and encouraged people to be ethical, and he urged them to teach and encourage others to do the same. In that way ‘through his followers he worked to spread his ethical activism out into the societies of his time’.10

Fronsdal has some very pertinent things to say on how activists would behave if they followed the ten precepts, which Buddhist activists would do well to read and reflect on. However, I am not convinced that encouraging people to treat one another well can be regarded as activism, no matter what the culture. A friend wrote the following to me after reading the previous article in this series, which I think is closer to the truth, and with which I will bring this article to a close:

Rather than social reform, the Buddha’s aim seems to have been twofold: firstly to create a space outside society – the community of his homeless wanderers – where hierarchies of power could be abandoned and transcended; secondly, to mitigate the harshness of worldly hierarchies by inculcating values crystallised in the Buddhist moral precepts.

Footnotes

- This is according to Bhikkhu Sujato, whose translation I will mainly use in this article.

- To read the sutta, go to https://suttacentral.net/dn26/en/sujato?lang=en&layout=plain&reference=none¬es=asterisk&highlight=false&script=latin

- Samaṇas, that is homeless wanderers, who practise the spiritual life under various different teachers.

- Samaṇas, that is homeless wanderers, who practise the spiritual life under various different teachers.

- The word translated as ‘follower’ is anuyantā, which can also mean ‘vassal’.

- See https://apramada.org/articles/the-buddhas-advice-to-the-vajjika-league

- See, for instance, Dhammapada verse 116 and this article: Ethical Beauty – Apramada

- To see how one immoral act leads to another, see the sutta itself: DN 26: Cakkavattisutta—Bhikkhu Sujato (suttacentral.net)

- Itivuttaka 42. https://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/kn/iti/iti.2.028-049.than.html#iti-042

- The Buddha as an Activist – Insight Meditation Center