The passage of A Survey of Buddhism (hereafter, ‘the Survey’) in which Sangharakshita explains the Buddha’s doctrine of the Middle Path is particularly brilliant, even by his standards. It is one of several examples in the Survey in which he takes a traditional and well-known Buddhist doctrine and reveals depths that are not plumbed in popular accounts of it. The Middle Path is, he tells us, almost always commented on exclusively from an ethical point of view, with the result that ‘One of the profoundest teachings of Buddhism is degraded to the practice of an undistinguished mediocrity’,1 amounting to little more than the truism that one should avoid extremes of behaviour. But in Sangharakshita’s exposition, ethics is but one of three ‘modalities’ of the Middle Path. The identification of these modalities and the connections between them reveals the true depth of the doctrine, and allows a fuller appreciation of the nature of Buddhist ethics by showing it in its proper context.

The presentation of this framework in the Survey is, as Sangharakshita says, ‘rudimentary’ — by which I take him to mean ‘consisting of first principles’ rather than ‘primitive’. Nevertheless, since the Middle Path, the two poles of delusion between which it navigates, and the three modalities on which they all operate, between them encompass all possible views about the nature of reality and the behaviours that follow from them, the possibilities for elaboration are virtually infinite. After giving a summary of Sangharakshita’s position I will therefore identify a number of points that particularly deserve such elaboration.

The Triadic Principle

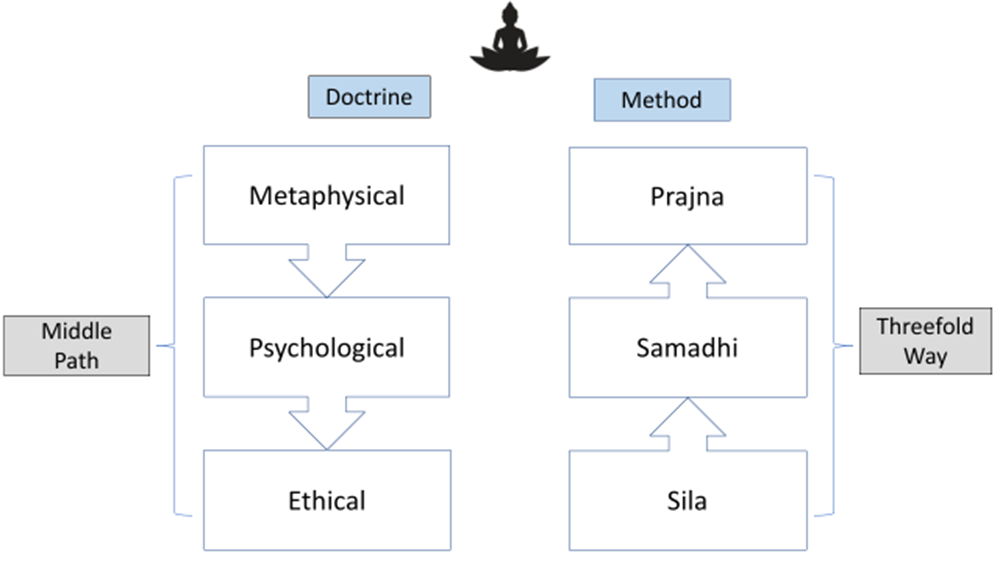

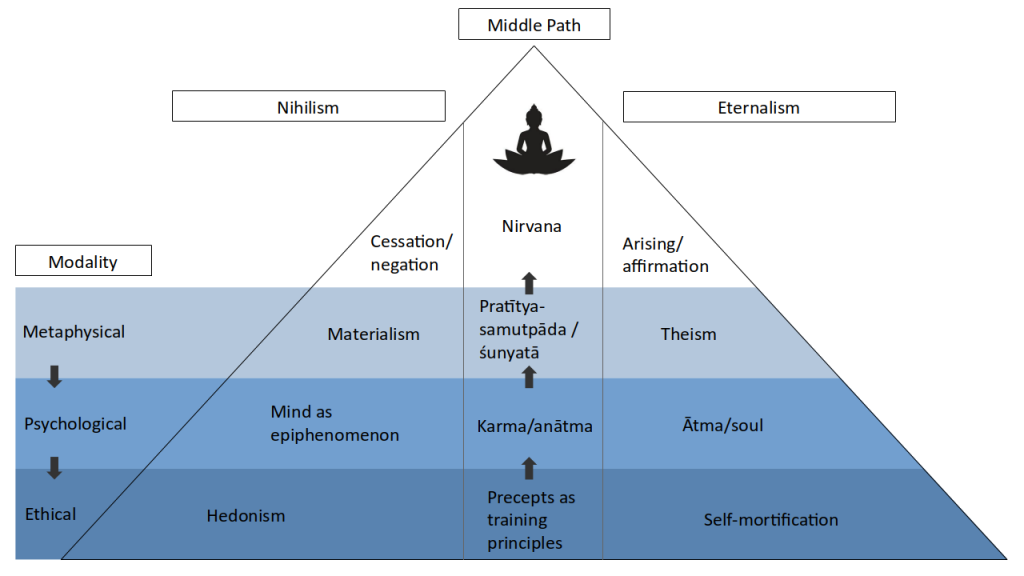

Sangharakshita’s main point seems to be that the Middle Path applies to the whole of the Dharma, in both its doctrinal and methodological aspects, and at every level of spiritual development. In its highest sense, he tells us, the Middle Path is equivalent to the realisation of nirvana itself. Since it transcends both affirmative and negative predications, nirvana is between, or better above, the extremes of existence and non-existence. This highest, transcendental aspect of the Middle Path manifests at a ‘lower’ level as the necessity of finding an intermediate position between extremes in every doctrine or method of the Dharma.

Just as the Middle Path manifests at a lower level, so the two extremes which are to be avoided have a ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ application. As we progress on the path the wrong extremes remain, but become subtler and more spiritually seductive, and the Middle Path between them more difficult to perceive. At their highest level the extremes manifest in such a subtle way that it may not be easy for us experientially to understand the distinction between them: ‘…on the right, eternalism in its subtlest and most principial forms: the Absolute, pure Being, Godhead, Divine Ground; on the left, the archetypes of nihilism: annihilation of the soul in God, the dissolution of the lower self in the Higher Self, the merging of the drop into the Ocean.’ These seem to be descriptions of deep meditative states. In the experience of such states there won’t be much or any conceptualization going on, but there may be a subtle clinging to the aspect of arising, and thus to eternalism, or to that of cessation, and thus to nihilism; and such subtle clinging may lead to subsequent expression in language that favours one or other pole. But the Middle Path holds itself aloof from these temptations, ‘untarnished by even the shadow of a positive or negative concept.’

This is the ‘triadic principle’ at its highest possible application. ‘Below’ this, Sangharakshita identifies three levels, or ‘modalities’, of the manifestation of this principle: in metaphysics, in psychology, and in ethics. In each modality there is a correspondence not only between the higher and the lower applications of the Middle Path itself, but between the higher and lower applications of the two extremes. We will now look at each of these modalities in turn.

Three Modalities

The transcendental aspect of the Middle Path consists of a direct penetration into the truth, in which even the subtle, spiritual manifestations of the extremes of eternalism and nihilism2 described above are transcended. This insight into the nature of things is supra-conceptual, but finds expression in concepts through such doctrinal formulations as pratītya-samutpāda, śūnyatā, and the term ‘Middle Path’ itself. These constitute the metaphysical modality of the Middle Path. Although a conceptual formulation, they represent an attempt to avoid the error of using the affirming and negating tendency of language as a descriptor of what is ultimately real. Or in Sangharakshita’s words, ‘Following the Middle Path in metaphysics consists in understanding that reality is not to be expressed in terms of existence and non-existence and in recognizing that the positive and negative indications of Nirvana, whether concrete or abstract, sensuous or conceptual, possess not absolute but only relative validity.’ Missing this Middle Path means veering either to the extreme of existence, in which the arising of phenomena is abstracted into an eternalist principle (such as God or the ‘Absolute’), or to the extreme of non-existence, in which the cessation of phenomena is abstracted into a denial of any higher moral or spiritual order.

Next, one’s metaphysical beliefs will inevitably find expression in one’s view of the human personality. The eternalist belief in an Absolute Being as the highest reality will be reflected in a belief in a fixed soul or self which constitutes our true nature. More specifically, it follows from a belief in a creator Deity that the human personality is a part of his creation, and typically that it shares some aspect of his divinity, such as immortality. On the other hand, if one’s view is nihilist one will tend to assume that the human personality has no higher significance. The most common nihilist view these days is ‘materialism’, which sees consciousness as a mere by-product of material processes. The Middle Path in this ‘psychological’ modality is the doctrine of anātmavāda, which corresponds to the metaphysical conception of śūnyatā. Anātma means not merely ‘no self’, as it is sometimes rendered, but rather ‘no fixed self’. It avoids both the nihilistic identification of all mental activity with the body, and the eternalist extreme of positing an unchanging entity such as an immortal soul that exists independent of the flow of mental and physical conditions of which a human being consists. As well as the correspondence between śūnyatā and anātmavāda noted by Sangharakshita, I would add that a similar correspondence may be seen between pratītya-samutpāda and karma, which together represent the dynamic aspect, as the former pair represent the static aspect, of their respective modalities.

Finally, one’s view about the nature of things in general, and of human nature in relation to that, will find expression in both the theory and practice of ethics. A nihilistic belief ‘will inevitably reduce man to his body and his body to its sensations.’ The meaning of life then becomes the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain. Contrariwise, a belief in an eternalist principle, and the related belief that what is essential in a human being shares in the nature of that principle, leads to the view that matter is ‘illusory or evil or both’, and the body comes to be regarded as ‘the principal cause of man’s non-realization of his identity with or dependence on the Divine.’ Spiritual life then becomes an attempt to dissociate from the body and its temptations. This leads in its extreme form to self-mortification — as was tried by the Buddha prior to his Enlightenment, and rejected as being worthless in the pursuit of the goal.

The Middle Path of Ethics

In the section of the Survey under discussion, Sangharakshita uses the Middle Path to introduce ethics as the first stage of the Threefold Way. It is illuminating to see the two teachings in relation to one another in their totality, since the different angles of approach to the Dharma that they represent correspond to the distinction between doctrine and method (as explored in the previous article in this series). The modalities of the Middle Path express a doctrinal descent, as it were, from spiritual insight to its metaphysical expression, and then from metaphysical principle to its application first to the nature and then to the behaviour of the individual. The Threefold Way expresses a methodological ascent from a training in behaviour, to a transformation of mind, to an illumination through wisdom by means of the contemplation of certain metaphysical truths. Considering the Middle Path and the Threefold Way in relation to one another makes it clear that there is no doctrine without method, and no method without doctrine. Doctrinal formulations have methodological implications, and the application of method must be guided by an understanding of doctrine. Therefore in practising the Threefold Way, only through a correct understanding of doctrinal principles, and a thorough application of those principles in experience, can progress from one stage to the next be made.

Fig. 1

Although Buddhist ethics may be expressed in various lists of numbered rules, it is more fundamentally an ethics of intention. An action is considered moral or immoral – or in Buddhist terminology, ‘skilful’ or ‘unskilful’ – according to the relative absence or presence of the three mental poisons of greed, hatred and delusion. This does not, however, mean that we can justify any behaviour on the grounds that our mental state was a skilful one, since there is a close connection between the quality of our mental states and the type of action that arises from them. ‘Deeds condense out of thought just as water condenses out of air.’ This means that an arhant is free not from the responsibility to behave skilfully, but from any struggle involved in doing so, since he is no longer subject to the mental states that underlie unskilful behaviour. His behaviour is ‘the spontaneous outward expression of an emancipated mind’, whereas the ethics of the worldling is ‘a disciplinary observance.’ Sangharakshita makes a comparison with the creation and enjoyment of poetry: ‘The arhant passes poet-wise from ‘inspiration’ to ‘expression’; the worldling reader-like from ‘expression’ to ‘inspiration’.’

The connection between mental state and action runs in both directions. It is not just that actions express mental states, they also induce them. For this reason, the adoption of codes of conduct as recommended by the Buddha is not an end in itself, but a means of developing the state of mind that naturally corresponds to those behaviours. Initially this must mainly take the form of restraint, because at the outset of one’s spiritual life unwholesome states of mind, from which unskilful actions arise, will usually predominate, and these need to be curbed (which explains the formulation of the Pali ethical precepts as abstention from unskilful conduct). With this as an indispensable foundation one can turn one’s mind to the cultivation of wholesome qualities, of which skilful action is the natural expression. Conscious cultivation of the wholesome being the essence of meditation, we can see how the first stage of the Threefold Way shades into the second. The practice of ethics in Buddhism is a means to establish oneself in the wholesome mental qualities that characterize meditative absorption, just as the development of those wholesome qualities is a means to the penetration into the nature of things through wisdom.

Fig. 2

Having now, I hope, grasped the basic framework of the triadic principle and its modalities, we can turn to some further implications of these ideas.

The Nature of Views

The first concerns the nature of views, regarding which a possible misunderstanding must be averted. It should not be thought that the two poles of wrong view are primarily an intellectual mistake, to be corrected merely by adopting a different philosophical position. The myriad varieties of articulated wrong view are expressions on the level of the rational mind of forces that lie much deeper in the psyche, and it is these that reveal themselves in behaviour as a bias towards eternalism or nihilism. Sangharakshita makes this point in The Three Jewels:

Usually we do not like to acknowledge, even to ourselves, that our attitude towards life is often no better than that of a pig rooting for acorns. Motives are therefore rationalised. Instead of admitting that we hate somebody, we say he is wicked and ought to be punished. Rather than admit we enjoy eating flesh, we maintain that sheep and cows were created for man’s benefit. Not wishing to die, we invent the dogma of the immortality of the individual soul. Craving help and protection, we start believing in a personal God. According to the Buddha, all the philosophies, and a great deal of religious teaching, are rationalisations of desires.3

But the fact that views are primarily sub-rational and only secondarily rational, far from discounting the importance of a clear rational understanding of Buddhist doctrine, in fact itself argues for it. For unless one consciously cultivates the right view that steers the Middle Path, one will unconsciously be dominated by wrong views that fall either side of it. Moreover, unless one is also deliberately making an effort to apply such right view to ethical practice, one’s behaviour will inevitably be captured by one or other extreme of wrong view. Clarification of view, and training in the behaviours that accord with that view, must go together.

Wrong View in Practice

Working with the Middle Path in its application to ethics means adopting the precepts as training principles, as well as being aware of when one is veering towards one or other wrong pole. But to understand what this looks like in practice another point must be addressed. When discussing the application of eternalism and nihilism to the ethical modality Sangharakshita talks only of the extremes of self-mortification and hedonism, but the issue is more subtle than that. In reality very few people practise such extreme asceticism or are willing to completely deny a moral order and embrace unrestrained hedonism. However, the less malignant neighbours to such extremes are much more commonly found. This will continue to be true for many who have adopted Buddhism and therefore do not subscribe to eternalist or nihilist philosophies in their articulated form, since these views have their basis in unconscious tendencies.

But though the tendencies themselves may be largely unconscious, our actions and motivations will reveal in which direction we are prone to veer from the Middle Path. An eternalist bias may manifest in feelings of guilt and inadequacy in relation to an authority that is projected ‘outwards’, and in myopic conformity with the rules and religious observances that are seen as stipulated by that authority, without the connection with the mind’s intentionality that makes such rules and observances genuinely transformative. A nihilist tendency is likely to be found in the rejection of perceived authority and the over-valuing of subjective feeling as a guide to action. Working with the Middle Path involves the development of the individual’s moral sensibility according to the objective standard of the precepts considered as training principles. This brings together and harmonizes the objective and subjective aspects of morality.

The fact that the extreme behaviours that align with each wrong view are relatively rare points us towards another important implication of these ideas. Morality is natural, part of the way things are, and intrinsic to consciousness as a potentiality; but neither eternalist nor nihilist views provide an adequate foundation for it, nor a means for its further development. We can see this if we look at extreme positions of both. An example of an extreme eternalist position would be that the good is whatever God wills. One’s duty as a part of his creation is to submit oneself to that will, whatever it is believed to be. As Sangharakshita says in The Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path,

when God himself tells you to do something the order obviously comes with a tremendous weight of authority behind it. Thus one does something not so much because it is good to do it but because one is asked to do it, even commanded to do it, by one in whom reposes all power and all authority in heaven and upon earth.4

Accordingly, the development of an individual’s own moral sensibility will not be seen as important, and the practice of morality will tend to consist in the following of commands, however arbitrary, that are seen as proceeding from the Deity. At best this means that, even if the commands happen to be good ones, they are not being followed entirely for the right reasons. At worst it means that any atrocities may be justified by a sanction that is believed to transcend human understanding. I am not suggesting that someone who believes in God will not be a sincerely good person – far from it – only that, if they are truly good rather than just good at following rules, they are to that extent close to the Middle Path as understood in Buddhism. Rather than the good being whatever God wills it to be, they must believe that God wills whatever is good. This establishes goodness as something independent of the notion of an omnipotent creator, and is a step towards abolishing the latter entirely.

An example of an extreme nihilist position would be that since only matter is real there is no such thing as morality. Aside from the fear of social retribution there is therefore no reason for individuals to curb whatever cruel or avaricious impulses arise within them. Mercifully, very few people seem willing to embrace this conclusion. Even the most committed materialist thinkers will not deny morality, but rather attempt to justify it on, for example, Darwinian grounds — as necessary for the survival of genes etc. Anything other than admit to a transcendent aspect of existence.

But although outright negation of morality is not common, there is plenty of evidence that the modern West, perhaps especially in the Anglosphere, is predominantly nihilist, living as it does in the aftermath of Nietzsche’s ‘Death of God’. The signs of this may be seen in the social sphere in the form of cultural relativism, and in the private sphere as rampant individualism. If there is no objective morality there is no standard to judge different cultures by: moral judgements are seen merely as cultural norms. Deprived of any objective sanction, morality revolves around the ‘rights’ of the individual, and the only inter-subjective moral duty is to fulfil one’s desires in a way that does not prevent others from doing the same. This ‘mere liberalism’ (as I call it) is meagre fare for the human heart, and leaves a spiritual vacuum into which rush ideologies of all kinds — communism, nationalism, feminism, environmentalism, etc. — all of which, while not necessarily lacking in their own virtues, in their extreme forms follow quasi-religious patterns and are clung to with a commensurate zeal. These are poor substitutes for the sublime, transcendent perspective offered by The Middle Path of the Buddha.

The Dialectic of View and Action

Considering the nihilist trend of the contemporary West brings us to another point of elaboration, which I have not heard stated before. In the passage we have been examining, Sangharakshita emphasises how moral action has its basis in metaphysical views. There is thus a ‘descent’, analogous to a logical deduction, from the universal to the particular. This is simultaneously a movement from the inner to the outer — from inward belief to outward expression. But surely, there must be a movement the other way also, induction-wise from the particular back to the general, and from the outer back to the inner. There must, in fact, be a dialectic between the two positions. The external conditions in which metaphysical views are enacted influence the direction off the Middle Path the views of a society and an individual are likely to veer, by serving either to confirm or to challenge those views.

It is perhaps already obvious how training in the precepts will support and reinforce a confidence in the very Middle Path of which they are the practical expression. But we can see the same feedback applying to the wrong poles also. An eternalist belief will lead, in extremis, to mortification of the flesh; and a condition in which sense experience is predominantly painful will reinforce an eternalist belief. For if the ‘self’ — the object of the second of the three modalities — finds nothing worth attaching itself to in the material world, it will tend to look beyond the material, to an eternal source of security.

Similarly, and more pertinently to the contemporary situation, I suggest a mutually reinforcing relationship between materialist philosophy and materialism as a lifestyle. It is surely not entirely an accident of history that an advance in material prosperity has been accompanied by a decline in religious belief. An ever-increasing mastery of the material world diminishes our interest in what may lie beyond it, and encourages the idea that nothing does. An unprecedented ability to provide the senses with endless gratification encourages us to invest in them as sources of enduring happiness, and blinds us to where true happiness lies. If this is true, it is not merely technology and consumerism that the West is exporting throughout the world, but also a disposition towards nihilist metaphysics.

The Middle Path in the Political Realm

Not the least fascinating thing about these ideas is that they show how theory and practice are mutually intertwined. Not only individual human lives, but entire cultures are shaped by views. Indeed, we can see the tension between the two poles of wrong view as perhaps the major factor at work in shaping contemporary political discourse. On pretty much any issue that can be named we will find that our view of it will depend upon whether we are looking from the side of nihilism or eternalism. Moreover, these two poles can on the whole be aligned with one or other end of the political spectrum between conservative and progressive, with more conservative views usually backed either by theistic assumptions or the remnants of them, and more progressive views often underlain by nihilism.

A belief in God will tend towards conservatism because the meaning of life is believed to be found beyond the world, which is by nature fallen and imperfect and therefore pointless to try to change. Also, as has been said, eternalism locates the source of morality externally, which tends to support cultures that are dominated by the blind authority of tradition. Despite an abundance of evidence to the contrary, existence itself, including the social order, must be just if God created it, and therefore is not for humans to question. The clearest example of this is the Hindu caste system, the most ancient unjust social hierarchy in existence, which is explicitly sanctioned by eternalist assumptions. With such a rationalisation in their minds, the beneficiaries of the system can turn a blind eye to the most appalling poverty and degradation, and the atrocities committed in the name of caste.

The opposite assumptions underlie much of ‘progressive’ politics. With a rejection of any higher authority, man becomes the measure of all things. Tradition itself is seen as so much dead weight to be jettisoned, and abstract ideals such as liberty and equality (or worse, ‘diversity and equity’) are treated not merely as useful political principles but as the highest values in existence. The result will be a society with increasingly limited horizons and ever fewer objects of reverence. Those seeking outlets for idealism will increasingly fixate on political causes as substitutes for religion — a phenomenon of which the twentieth century offers ample examples, and which is common enough in our own times.

Without wishing to get too entangled in high philosophy, the role played by the idea of ‘free will’ in shaping political views sheds further light. The idea arises as a theoretical necessity to reconcile the eternalist notion of an unchanging soul with that of moral choice. The point here to emphasise is that free will, since it is a property of an immaterial soul, must be exercised independently of empirical conditions. The application of this belief in the political realm leads at its best to an emphasis on the moral agency of the individual, but at its worst to a disregard of the truth that moral agency itself requires certain external conditions in order to become operational. Neglect of this latter point entails one of the besetting sins of the political right, namely the rejection even in principle of social engineering to improve the lot of the disadvantaged, since all they need is to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. The opposite sin besets the left, which tends more towards the nihilist pole. While one virtue of left-wing thought is the recognition of how lives are shaped by social conditions, the extreme of this is a tendency to reduce a human being purely to the social conditions that created him (or her), which denies his individual agency and thereby his humanity.

Buddhists should take what is valuable from these positions while avoiding the pitfalls. The capacity for moral choice is innate to consciousness as a potentiality, but this can only be actuated if consciousness has developed according to certain conditions, both external and internal. There should therefore be neither a neglect of the importance of individual agency, nor of the broader social conditions that make possible its exercise, and the piecemeal improvement of society towards that end. Buddhists should believe that it is possible and desirable to bring about a more just and humane society, but that this requires an allegiance to a moral perspective which is ultimately transcendent in origin, and cannot be exclusively identified with any position on a political spectrum.

Before concluding let us return to Sangharakshita, whose summary of his own exposition we should now be well placed to understand.

The lower, that is to say, the relatively more concrete and more highly differentiated manifestation of a principle, cannot be understood more than superficially in the absence of an understanding of the manifestation of the next in order above it; whereas the knowledge of the higher contains principially5 the knowledge of the lower, and the realization of the highest, comprehension of all.

Since the Middle Path and the two poles between which it steers encompass in fundament all possible views, the ‘relatively more concrete and more highly differentiated’ manifestations of them are virtually unlimited, and include every particular ethical issue in the social and political realms. Whether sex should be confined to marriage for the purposes of procreation, or freely explored by the individual as a valuable end in itself; whether a foetus possesses an immortal soul and should therefore have the full protection that the law offers to human beings, or treated as a disposable waste product; whether the environment was placed at the service of humanity by its creator, or, rather, whether humans are a parasite whose very existence is a threat to a natural world which would have been better off without us: in each of these issues and many more, the various positions taken are deductions from metaphysical assumptions. Small wonder that there should be so much polarisation around such issues, when the opposing positions are expressions of irreconcilable and equally mistaken views about the nature of existence itself. Therefore, although the polarisation will be felt in relation to particular issues, the far deeper issue is the fundamental view about existence, which expresses itself in relation to the particular. It is this which Buddhists most need to address by propounding the Middle Path as vigorously and skilfully as possible. For this purpose, Sangharakshita’s treatment of this fundamental doctrine, with his account of the ‘triadic principle’ and the three modalities on which it operates, is the profoundest of which I am aware and deserves to be far better known, both by fellow Buddhists and by anyone who may be seeking a spiritual path that avoids the trappings of theistic religion.

Footnotes

- Unless otherwise stated, all quotations are from A Survey of Buddhism, Section 16.

- I follow Sangharakshita in using ‘nihilism’ to translate ucchedavada, one of the two poles of wrong view between which practitioners of the Middle Path must steer. Probably ‘annihilationism’ would be a more accurate translation, since ucchedavada literally means ‘cutting off’ – implying the annihilation of the life-principle at the point of death. This of course raises the question of rebirth, which indeed seems curiously absent in Sangharakshita’s exposition.

- Sangharakshita, The Three Jewels, p55-56

- Sangharakshita, The Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path, p528

- The term ‘principially’ is not in current use. In its archaic usage ‘principial’ meant ‘elementary’, but Sangharakshita’s use of it to mean ‘pertaining to principle’ seems to be particular to him. It is, however, such a useful coinage that one can only hope it catches on.