Themes from A Survey of Buddhism – Part Three

The full title of the book commonly known as ‘the Survey’ is A Survey of Buddhism: Its Doctrines and Methods through the Ages. As well as being named in the title, the distinction between doctrine and method is explained in Chapter One, and referred to throughout the book. In the first article in this series, doctrine and method were identified as one of a number of what I called ‘dyads’ to be found in the book; and I defined a dyad as ‘a pair of corresponding terms, principles, ideas, or archetypes, which arise from the nature of human understanding, and influence the way the Dharma is understood and finds expression.’ Although mentioned there, this dyad is particularly rich in significance, and warrants the further explication I shall give it in this article. I shall do so firstly by way of commentary on the paragraph of the Survey in which the distinction between doctrine and method is made, since it is so dense with meaning that the reader could be forgiven for not taking it all in without careful reflection and even some guidance. Secondly, I shall explain the context in which the distinction is introduced, which is to elucidate the Four Noble Truths. Sangharakshita’s account of this ubiquitous teaching carries the bold implication that it has undergone thousands of years of grave misrepresentation resulting from a failure to observe the very distinction under discussion, which highlights the crucial importance of that distinction. Thirdly, I shall explore some further implications of these ideas. In particular, I shall explore their link with Sangharakshita’s teaching on the progressive trend within conditionality (as outlined in the previous article), and the relation of that to some aspects of his later thought. We shall thereby range rather widely, and I only hope that this will communicate the richness of the theme, rather than bewilder the reader with variety.

Doctrine and Method in the Survey

Sangharakshita begins:

Throughout the entire Buddhist tradition there runs a clear distinction between what pertains to doctrine, theory, or rational understanding, on the one hand, and what pertains to method, practice, or spiritual realization on the other. The Pāli texts of the Theravāda Tipiṭaka abound in references to the ‘doctrine and Discipline’ (dhamma-vinaya). Similarly, the Mahāyāna Sanskrit texts speak repeatedly of wisdom (prajñā) and skilful means (upāya) as the twin aspects of the Buddha’s teaching.1

He doesn’t further define the distinction in the Survey, perhaps considering his meaning sufficiently clear. In my article ‘The Transcendental Principle and the Dyads of the Understanding’ I offered a succinct, if less than fully adequate, definition:

I suggest that we can summarize the distinction as consisting on the one hand of what may in truth be said about the nature of things, and on the other of what must be done in order to realise that truth, or experienced as a result. The former pertains more to the objective pole of experience, the latter to the subjective.

A fuller definition is given in the following passage from In the Sign of the Golden Wheel (Sangharakshita’s third volume of memoirs) in which he recounts a lecture, given in the same year he was writing the Survey.

In the first lecture, ‘Buddhism as Doctrine and as Method’, I emphasized that the criterion of Truth was pragmatic, and that as Doctrine Buddhism might be defined as a body of teachings the intellectual acceptance of which tended to lead to a course of action eventually resulting in the attainment of Enlightenment. As was famously illustrated by the Buddha’s ‘Parable of the Raft’, Doctrine had only a relative and provisional value, and it was because they were convinced of the relativity of their own doctrines that Buddhism could be undogmatic and, therefore, tolerant. The course of action following from acceptance of the doctrines of Buddhism, and resulting in the attainment of Enlightenment, was threefold, consisting of ethics, meditation, and wisdom. All the methods of Buddhism, comprising its entire practical side, could be included under one or another of these heads. As Method, Buddhism therefore comprised all those practices that were conducive to Enlightenment.2

Definitions having been dealt with, we can proceed to more interesting matters. The passage from the Survey continues:

It should be noted that we speak of a distinction, not of a difference; for here we are concerned not with a division between different things of the same order, or even between different parts of the same thing, but simply with a certain doubleness of aspect under which the Dharma, while remaining in itself unaffected, necessarily presents itself to human understanding.

We are not talking about a difference, whether between ‘different things of the same order’ or between ‘different parts of the same thing’. An ‘order’ is general, and sub-divides into types of things, whereas a ‘thing’ is particular, and sub-divides into parts of that thing. For example, two breeds of dog belong to the same ‘order’, whereas a dog’s tail and teeth are different parts of the same thing. In both cases a more inclusive category may be deductively sub-divided into mutually exclusive sub-categories.

Rather, we are talking about a distinction. The Dharma is not a conceptual category that can be sub-divided into doctrine and method, or any other mutually exclusive sub-categories or parts. It is more that from the limited perspective of human understanding, the Dharma, while itself being indivisible, appears simultaneously in these two ways. This ‘doubleness of aspect’ – as with all the dyads I have been explicating in this series – arises from the interaction between a doubleness in human understanding and the irruption into it of something entirely beyond its forms. The result is that the view we have of the Dharma differs according to which of the two perspectives we see it from. Thus,

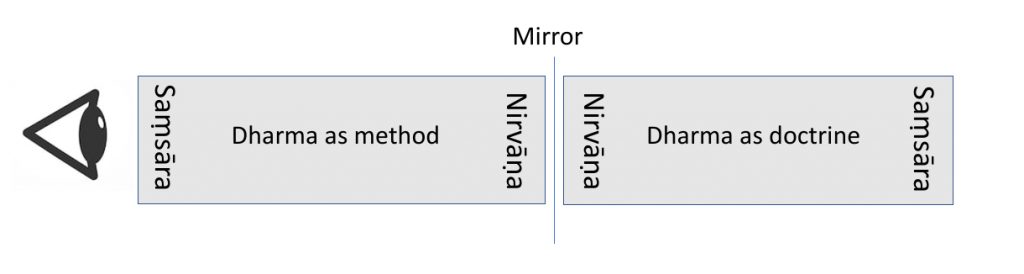

Corresponding to these two aspects of the intrinsically impartite Dharma there are two procedures, methods of approach, or points of departure, the ‘view’ of the Dharma obtained from one differing from that obtained from the other in much the same way as the countryside as seen from the top of a high mountain differs from the countryside as seen from the mountain’s foot. Or each view is ‘reversed’ in relation to the other, like the image of a thing reflected in a mirror: that part of the object which is nearest to the spectator, supposing the object to be between him and the mirror, appears as furthest from him in the reflection. If the Dharma is viewed under the aspect of wisdom, then Nirvāṇa is ‘near’ and saṃsāra ‘far’; if under the aspect of method, then saṃsāra is ‘near’ and Nirvāṇa ‘far’.

Here we are offered two metaphors. Firstly, doctrine corresponds to seeing the countryside from the top of the mountain, because one’s view is vaster, and the truth may be discerned in everything equally – just as (to extend the metaphor) the sunlight lies evenly over the terrain surveyed from whatever peak one might surmount. Method corresponds to seeing the countryside from the foot of the mountain, because, although one cannot see as far, one sees more of the details of one’s immediate surroundings, especially those details that are relevant (in the case of the metaphor) to the ascent of the mountain, or (in the case of the Dharma) to progress on the Path.

The second metaphor is more subtle, and deals not merely with the distinction between doctrine and method but also with the intimate and necessary connection between them. It is of something standing between a mirror and a spectator, such that the part of the object that is nearest to the spectator appears furthest away in its reflection (See fig. 1). This illustrates the obscure statement: ‘If the Dharma is viewed under the aspect of wisdom, then Nirvāṇa is ‘near’ and saṃsāra ‘far’; if under the aspect of method, then saṃsāra is ‘near’ and Nirvāṇa ‘far’.’

(Fig 1).

Sangharakshita explains himself thus:

Since on the plane of his compassionate action the Buddha was concerned with the ‘realities’ of the immediate human situation, not with things as they might or ought to be but as they actually are, he was obliged to present the Dharma more often under the aspect of method than under that of doctrine. Worldlings could be shown the mountain peak only as it appeared from the valley in which they dwelt. Nirvāṇa must be presented as ‘far’ and saṃsāra as ‘near’. The ‘world’ being a positive datum of experience, and mankind having on the whole no knowledge of anything beyond the world, Nirvāṇa had necessarily to be described to them in terms of the cessation of the world, hence in a predominantly negative manner.

In other words, for as long as we are worldlings ‘the world’ is all we know. To us it is ‘near’. And since nirvāṇa is beyond anything that is known to us, it must be presented to us as ‘far’, and as a negation of that with which we are familiar. Regarding why nirvāṇa is near and saṃsāra far when the Dharma is viewed under the aspect of wisdom Sangharakshita does not elaborate (nor is it immediately obvious why he uses the term ‘wisdom’ here, rather than ‘doctrine’). But perhaps we can call to mind that elsewhere in the Survey he defines wisdom as consisting of ‘insight into the real nature of phenomena.’ The truth about phenomena applies as much to the unenlightened as to the Enlightened, but for the latter it is known in immediate intuition, and is thus ‘near’, whereas the fabricated, painful world of the unenlightened, having been left a long way behind, is seen as ‘far’.

To further explore what is being got at here let us borrow some language from theology and ask, is nirvāṇa a transcendent goal or an immanent truth? Is it to be found above and beyond us, or here and now? The answer of course is both. Or rather, both are valid, and indeed necessary, ways of conceptualising it. But in the early stages of the path our attention needs to be more on nirvāṇa as a transcendental goal. We need to recognize, to the extent that we are able, the gulf that separates us from it. Relating to the goal in this way, we will place the emphasis more on method than doctrine, because a recognition of the distance we have to travel focuses our attention on the practical steps required to make headway. But if the goal remains always transcendent, we shall be destined forever to move towards it, but never reach it. For this reason, as our Dharma practice progresses, we must also come to recognise nirvāṇa as an immanent realisation. This shifts our attention more towards doctrine, because that describes in its barest form the nature of things as seen by the eye of wisdom (hence Sangharakshita’s change of terms from ‘doctrine’ to ‘wisdom’, noted above). But if the danger of remaining solely focussed on nirvāṇa as transcendence is that we won’t bridge the gap between the path and the goal, then the (far more real) danger of adopting an immanence perspective prematurely is that of failing to recognize how much transformation through the application of method is required, and of mistaking a rational comprehension of doctrine for spiritual insight into it, or otherwise aggrandizing limited spiritual understandings with a status beyond anything they deserve.

If I may be permitted a personal reminiscence, the changeable nearness and farness of nirvāṇa and saṃsāra was mentioned to me by Sangharakshita more than fifty years after he wrote the Survey. He considered it essential for spiritual progress that we recognise how far we are from Enlightenment. If memory serves, his words were: ‘If we think Enlightenment is near, it is far; but if we recognise it as far, it may just be near’. This cryptic comment was prompted by people claiming certain levels of spiritual attainment, of which he clearly did not approve.

Philosophical Language

To complete our account of the passage upon which I have been commenting, we must now retrace our steps a little, and deal with a sentence that I left out. If the passage is difficult because of the subtlety of the point, it is hardly made easier by the inclusion in it of the following abstruse statement, involving some quite specialized philosophical language:

The distinction with which we are here concerned is obviously of the same order as the distinction between logical priority and priority in experience, between the a priori and the a posteriori kinds of reasoning, and between the deductive and inductive methods of arriving at truth.3

The doctrinal aspect of the Dharma is expressed in abstract terms, and thus may be compared with rational, a priori knowledge and with deductive logic.4From the other side, the methodological aspect of the Dharma prioritises immediate experience, which can be compared with a posteriori knowledge, and with the inductive method, because general truths about the nature of things are reached ‘bottom up’ rather than ‘top down’, i.e. through first examining particular examples in experience, and advancing from there to an appreciation of the general principles which they exemplify. But, while these correlations do hold up, and may be illustrative for those familiar with the terms, they should not be thought of as essential for understanding the main point, and those not so familiar can safely pass them over.

With this explanation to help us, we should now be in a position to understand the final sentence in the paragraph.

Thus for purely practical reasons the Dharma confronts humanity under the aspect of method, while the sāsana or ‘dispensation’ which is the current manifestation of the Dharma under the modes of space and time appears as possessing a predominantly empirical, inductive, and a posteriori character.

The Four Noble Truths

So far I have prescinded the passage in question from its context, in order to give it detailed examination. But the context is even more important than the passage itself, and indeed reveals more of its full significance, and it is to this that I shall now turn. The distinction between doctrine and method is introduced to elucidate one of the most ubiquitous and characteristic teachings of Buddhism, namely the Four Noble Truths, of dukkha (suffering), its origin, its cessation, and the way leading to its cessation.

To begin, let us give more specific content to the category of doctrine. As we saw in a previous article, Sangharakshita identifies pratītya-samutpāda, the principle of universal conditionality, as the unifying doctrine of Buddhism – the touchstone against which the legitimacy or otherwise of all developments in Buddhist doctrine may be tested. He also distinguishes between pratītya-samutpāda considered as a transcendental reality, and as a general formulation. Regarding the latter, the formulation may be presented as consisting of four stages:

(1) Of any thing that exists, or any event that occurs, (2) conditions may be discovered upon which it depends. (3) Those conditions not existing or being removed, (4) the thing does not exist, or the event does not occur.

Since this is expressed at the utmost level of generality, it refers to no particular thing or event. The formula may be applied to any specific phenomenon, along with the conditions particular to the arising of that phenomenon.

Compare this with the Four Noble Truths, which are usually stated as (i) suffering, (ii) its cause, (iii) its cessation, and (iv) the way leading to its cessation. Sangharakshita points out that only the first of these has a definite content. The rest are a variation on the general formula of pratītya-samutpāda as just described (albeit with the third and fourth stages reversed). The same formula can be applied to anything, with only the first of the truths being varied (and indeed, Sangharakshita gives an example from the Scriptures of the formula being applied to a succession of different phenomena).

What he is suggesting is that the Four Noble Truths were originally a variation of the general formula of conditionality, but that the distinction between the doctrinal formula and its methodological applications was lost sight of, with the result that the formula eventually became exclusively identified with one application. So entrenched has that identification become that we cannot dispense with it, and must continue to see the Noble Truths as referring specifically to pain and its cessation. But we are in danger of falling into ‘one-sidedly negative’ interpretations of Buddhism unless we do so with the correct understanding of the distinction between doctrine and method. Sangharakshita repeatedly insists that the identification of dukkha as the first Noble Truth proceeds from considerations of method rather than of doctrine,5 and warns us that ‘Unless this distinction is made and continually borne in mind serious misrepresentation and distortion of the Dharma will inevitably ensue.’ A common example of such distortion is the idea that Buddhism is pessimistic. This arises from the mistaken assumption that the Noble Truth of dukkha is a metaphysical statement, belonging to doctrine, and that it invites us to see reality as a whole as painful. Rather, it is an attempt, for methodological reasons, to draw our attention to one highly significant aspect of experience.

Sangharakshita identifies two reasons why dukkha is the methodological starting point. Firstly, being directly experienced, the feeling of dukkha, whether physical or mental, can hardly be doubted by the sceptical intellect. It is moreover a psychological fact that it is dukkha that motivates all philosophical enquiry and religious aspiration, since if we were perfectly at peace with our existence, we would feel no compulsion either to explain or to reconcile ourselves to it. Secondly, it is not merely the rational mind to which Buddhism aims to appeal, but the emotional and desiderative aspects of the psyche; and since, as Sangharakshita tells us, ‘it is [man’s] desires, his experience of pleasure and pain, which ultimately determine his behaviour, it is only by somehow appealing to and utilizing them that human behaviour can be influenced and changed.’

Nor is the significance of this enquiry confined to the first of the Noble Truths. For just as it was a matter of method that dukkha was emphasized as the first of the Noble Truths, so it is a matter of method that the third truth consists of its cessation. Dukkha is merely an aspect of existence, albeit one that from a methodological point of view it is necessary to pay particular attention to. Considered from the point of view of doctrine, however, it is not merely dukkha that ceases with the attainment of Enlightenment, but saṃsāra in its totality. In this regard, ‘The third truth therefore corresponds to the purely negative and transcendental aspect of nirvāṇa’. But, as has been made clear in the previous articles in this series, Enlightenment is not merely a negation but has a spiritually, as distinct from a conceptually, positive character. Therefore, ‘Just as the first truth relates to one aspect only of phenomenal existence so the third truth is concerned with one side only of the spiritual life… Craving having been posited as the cause of suffering, the nature of the general formula constituting the doctrinal framework of the four truths requires that the cessation of suffering should depend upon the cessation of desire. The positive side of the spiritual life has not been mentioned.’

Before proceeding further let us sum up. The Dharma can be considered under the aspect of doctrine or under the aspect of method. Considered as doctrine, we express pratītya-samutpāda in an abstract formula. In its application to the spiritual life, this can be seen ‘negatively’, as the cessation of all conditions pertaining to saṃsāra, or ‘positively’, as the recognition that certain conditions give rise to nirvāṇa. Considered as method, we identify specific examples of the doctrinal formula which it is most useful to dwell upon. These too can either be particular aspects of the saṃsāra which are to be transcended, and thus ‘negative’, or qualities to be cultivated on the path to nirvāṇa, and thus ‘positive’.

Now, the Four Noble Truths may be seen both as doctrine and as method. Seen as doctrine they express a general formula describing the existence, cause, cessation, and means to the cessation, of any phenomenon whatsoever. Seen as method, dukkha is identified as that aspect of saṃsāra which needs to be held in mind. According to the formula, this gives us the cessation of dukkha as the methodological expression of the third of the truths. But this only expresses method in its negative aspect, in terms of cessation. The positive aspect, of the identification of the conditions that give rise to nirvāṇa, is not thus far included.

Next, remember that the failure to recognise the distinction between the Dharma considered as doctrine and considered as method has led to a misunderstanding of the nature of the first Noble Truth (of dukkha), as a metaphysical statement about the nature of existence as a whole, rather than a methodological statement about that aspect of existence which in practice we need to be most aware of. Corresponding to this is a misunderstanding about the third truth (of the cessation of dukkha), namely that of seeing it as a doctrinal counterpart of the first, rather than a methodological one. The result is that, to the general bias of seeing the spiritual life only in terms of negation, is added the specific one of seeing it solely as an escape from dukkha. The third Noble Truth, as commonly understood, therefore combines two connected mistakes that Sangharakshita identifies as having entered the Buddhist tradition early: the over-focus on negative formulations of the path, and the failure properly to observe the distinction between doctrine and method.

This may seem rather technical, but it is important to clear up because theoretical misunderstandings have practical ramifications. If we wrongly see the third truth of the cessation of dukkha as a doctrinal teaching rather than a methodological one, we are in danger of seeing nirvāṇa merely as absence of pain, and our spiritual life will end up consisting of what Sangharakshita calls ‘the studious avoidance of painful experiences.’ The real reason we are encouraged to pay attention to dukkha is that ‘it is a sign that we are not living as we ought to live… What we really have to get rid of is not suffering but the imperfection which suffering warns us is there.’ Moreover, ‘The essence of Buddhism consists not in the removal of suffering, which is only negative and incidental, but in the attainment of perfection, which is positive and fundamental.’ This attainment of perfection should not be done merely for the sake of avoiding suffering, but ‘simply and solely for its own irresistible sake.’

This is a deep idea, which deserves a bit of explication, especially as it further draws out the significance of the doctrine/method distinction. Since the basic condition of saṃsāra is the attachment to ego-identity, the communication of the Dharma must, as a matter of method, address itself to the desires arising from such attachment, especially the desire not to suffer. The ego is offered a kind of bargain with reality: ‘If you do x, y and z, you won’t suffer any more.’ While true on its own level, this bargain is both limited and limiting. It makes our connection with the transcendental goal of the Dharma conditional on whether the desires of the ego are met, whereas the spiritual life is lived precisely to overcome ego-attachment. Therefore, as practice develops and the ego becomes less dominant, the transcendental truth of the Dharma and the state of perfection that coincides with its realisation are increasingly embraced unconditionally, and freedom from dukkha becomes a by-product rather than the main motivating force. This shifts one’s attention away from method and towards doctrine, which describes the truth of things irrespective of its relation to human motivation.

Doctrine and Method Unified

The distinction between doctrine and method, as well as being explored with remarkable acuity in the section we have been discussing, is referred to repeatedly throughout the Survey. The passage in which the distinction is first made makes it clear that doctrine and method are not only distinct, but also intimately connected, since they are mutually entailing aspects of the Dharma’s expression in forms comprehensible to human intelligence. For this reason it is only half the truth to say, as I have sometimes heard, that all doctrine is for the sake of method. It is equally true that all method is for the sake of doctrine – for the sake of understanding its true meaning and significance. To put it aphoristically, one could say that doctrine without method is useless, while method without doctrine is blind.

But the intimate connection between these two aspects of the Dharma gives rise to an issue that is not adequately resolved in the Survey. For surely, we cannot fully understand the nature of the connection between doctrine and method until we know in what they individually consist. We are given the unifying doctrinal principle of the Buddhist tradition as pratītya-samutpāda, which shows us half the picture. But what of method? Is there a unifying principle that governs that partner in the dyad?

Here, more than anywhere else, we encounter a discrepancy between Sangharakshita’s account in the Survey and his later thought. It comes down to this: when he wrote the Survey, he had not realised the full significance of Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels. Recognizing a need for a methodological unifying principle, but not yet having arrived at the correct one, he argues, not entirely convincingly, for the Bodhisattva Ideal as filling that position.

Since Going for Refuge was not identified by Sangharakshita as the true methodological unifying factor until much later, he was not able to examine the connection between this and pratītya-samutpāda in the Survey. A thorough treatment of the subject would require not only a full exposition of his thinking on Going for Refuge, but also a detailed study of pratītya-samutpāda in relation to it, which is far beyond the scope of this article. But the subject seems like such a crucial one, that it is worth seeing if we can identify the most essential points. Although to my knowledge he did not deal with the question exhaustively anywhere in his later writings, he left enough to serve. And in fact some of his later thinking on Going for Refuge seems to me a fusion of doctrine and method into a single unifying perspective6

We turn to Sangharakshita’s remarkable little book, The History of My Going for Refuge, for a passage that illuminates this point. We saw in the previous article that the positive trend within pratītya-samutpāda is one of his hallmark teachings. This ‘spiral’ conditionality finds methodological application in (amongst other formulations) the twelve ‘positive’ nidanas: a series of progressive stages to be traversed on one’s way to the goal, in which each stage arises in dependence upon the one that precedes it. The first two positive nidanas are suffering and faith, which means, as he says, ‘faith in the Three Jewels, as representing the highest values of existence’. And since this faith manifests as a commitment to those ideals; and since commitment to the Three Jewels is what Going for Refuge means, we may conclude that ‘the act of Going for Refuge is identical with the arising of faith in dependence on suffering’. However, because the positive nidanas represent ‘not only a progressive but also a cumulative series’, the act of Going for Refuge in fact runs through them all, and is therefore, by implication, essential to the whole of the Dharma considered under the aspect of method. This clearly demonstrates the close connection between Going for Refuge and conditionality in Sangharakshita’s particular understanding, and thus the link between doctrine and method.

But Sangharakshita goes even further. Having identified Going for Refuge as the central and definitive act of the Buddhist life and described it as the primary condition underlying the traversing of the positive nidanas, he extends its meaning still further, and speaks of a ‘Cosmic Going for Refuge’. By this he means not just the Higher Evolution, in which man becomes aware of and responsible for his own development, but the entire process of evolution itself, lower and higher.

Looking at this process, what one in fact saw was a Going for Refuge. Each form of life aspired to develop into a higher form or, so to speak, went for Refuge to that higher form. This might sound impossibly poetic, but it was what one in fact saw. In man the evolutionary process became conscious of itself; this was the Higher Evolution. When the Higher Evolution became conscious of itself (and it became conscious of itself in and through the spiritually committed individual) this was Going for Refuge in the sense of effective Going for Refuge. Through our Going for Refuge we are united, as it were, with all living beings, who in their own way, and on their own level, in a sense also went for Refuge. Thus Going for Refuge was not simply a particular devotional practice or even a threefold act of individual commitment, but the key to the mystery of existence.7

It is through ideas such as this that the connection between doctrine and method reaches its zenith, and the line separating one from the other is at its thinnest. This zenith may be approached from either the side of doctrine or of method, with the distinction between the two becoming more transparent as they are each given more content. For convenience of exposition I shall identify four levels of both, with which this article concludes.

- Doctrine may first be described as the objective aspect of the Dharma, and as consisting of what may be said about the nature of things, insofar as language may be used at all. Method may be described as the subjective aspect of the Dharma, consisting of what must be done in order to traverse the path, and what may be experienced along the way.

- The primary doctrinal formulation of the Dharma is pratītya-samutpāda, the law that all things arise in dependence upon conditions. The primary methodological principle is Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels.

- Pratitya-samutpada has both a cyclical and a progressive trend. This means that the possibility of a process of higher development towards nirvāṇa is part of the way things are. Going for Refuge entails a conscious alignment of oneself with the progressive trend within pratītya-samutpāda.

- The notion of a progressive trend may be extended beyond the particular series of stages that must be traversed by the spiritually committed individual, to include all conditions within reality that make Enlightenment possible. This was described by Sangharakshita in his later thought as the dharma-niyama. And individuals who Go for Refuge, in becoming aware of themselves as being driven by an urge to self-transcendence and to the manifestation of a higher order of consciousness, can empathically extrapolate outwards to see this same urge reflected, to different degrees of development, in all phenomena. This is what Sangharakshita meant by ‘Cosmic Going for Refuge’. According to this perspective, it is not so much that we Go for Refuge, but that existence itself does so, and this becomes a conscious process in and through us. Going for Refuge is part of the way things are, and is identical with the progressive trend of conditionality. Doctrine and method are here united at the highest conceivable level.

Photo by Tanya Nevidoma on Unsplash

Footnotes

- Unless otherwise stated, all quotations are from A Survey of Buddhism, Section 15.

- Sangharakshita, In the Sign of the Golden Wheel, Complete Works volume 22, p268-9

- I have one slight quibble with Sangharakshita on this point. He describes a priori and a posteriori as “kinds of reasoning”, and deduction and induction as “methods of arriving at truth”. This is surely back to front. Deduction/induction are methods of reasoning, and a priori/a posteriori are kinds of truth, or better, of knowledge. While it is meaningful to speak of a priori and a posteriori reasoning, they are one or the other based more fundamentally on which kind of knowledge is the starting point for one’s reasoning.

- In the case of deductive logic such abstract formulae have the status of a priori truth. The qualification I would add is that the formulae of logic are not necessarily claims about the nature of reality (merely about the nature of logic), whereas Buddhist doctrine is such a claim. It would therefore push the comparison too far to say that Buddhist doctrine is true a priori. The most one can say is that if Buddhist doctrine is true universally, we know a priori that it is true particularly, because the particular must be contained under the universal.

- Dukkha, as well as being one of the Noble Truths, is of course also a lakshana, raising the question of whether it is being treated as doctrine or as method there too. In The Three Jewels Sangharakshita makes the following interesting statement regarding aniccata (impermanence): It ‘occupies a position as it were intermediate between the characteristics of anatman and duhkha, the one representing a higher, the other a lower, degree of generality of the same truth.’ This perhaps implies that anatman is to be considered doctrine, dukkha method, and aniccata a combination of both.

- ‘Revering and Replying Upon the Dhamma’ by Subhuti deals with this topic, and was in fact based on discussions with Sangharakshita.

- Sangharakshita, A History of My Going for Refuge, Complete Works volume 2, p482