Community is an outward and visible sign of an inward and invisible grace, the flowing of personal identity and integrity into the world of relationships.

Parker J Palmer1

In the first two articles in this series I discussed the nature of tribes and individuals respectively, and in this article I explore another category — spiritual community. This article is in four parts: in the first I explain what a spiritual community is and how it differs from a group or tribe. In the second I briefly discuss the influence that the spiritual community has, or can have, on the group, and vice versa. In parts three and four I take two specific instances of this mutual influence; in part three I discuss the way a particular group has been adversely affecting the spiritual community to which I belong, while in the fourth part I write about a specific spiritual community and the positive effect it had on the society in which it lived.

What is a Spiritual Community?

I want to begin by recalling Karl Jaspers and his theory of the Axial Age — roughly the time between 800-200 BCE — when a few outstanding people first emerged from group consciousness into individuality. Most if not all of those individuals had a sense of something ‘higher’ or transcendent, and they taught that it’s possible to be in touch with and to experience whatever that might be. In fact attempting to do so was, for them, the most important thing a human being could do. As Jaspers put it, the individual

…longs for liberation and redemption and is able to attain to them already in this world — in soaring toward the idea, in the resignation of ataraxia,2in the absorption of meditation, in the knowledge of his self and the world as atman, in the experience of nirvana, in concord with the tao, or in surrender to the will of God.

These paths are widely divergent in their conviction and dogma, but common to all of them is man’s reaching out beyond himself by growing aware of himself within the whole of Being and the fact that he can tread them only as an individual on his own.3

Jaspers’ insight into the great individuals of the Axial Age is astonishing, but the last clause in this quote is only half true. It’s true that we can only tread the path as individuals, that is, having made up our mind to do so independently, but it doesn’t follow that we therefore have to walk that path alone. In fact we’re much more likely to make spiritual progress in communication and cooperation with others. First, we need a teacher, someone who has trodden the path before us, and who can guide us along the way. And then we need to be in communication with others who are also trying to tread the path, because they can help, support, and inspire us, especially in those times when the going is hard. In other words, we need spiritual community. And this is in fact what we see in accounts of the Axial Age: individuals attracted others who tried to follow in their footsteps. They formed spiritual communities.

Spiritual communities are not to be confused with religious groups though. Spiritual communities consist of individuals, or at least aspiring individuals, and they encourage individuality. Groups reward conformity and discourage dissent, so they aren’t particularly interested in individuals. Because few people decide to take up the spiritual life, spiritual communities are very rare and are usually small, while religious groups are very common, and they tend to be very large, with the biggest ones boasting millions of members. Some religious groups may be positive groups, in that they recognize the value of individuality and support those who wish to become individuals. But that isn’t always the case, and in fact some religious groups seem to be, I’m sorry to say, negative groups. However, spiritual communities may exist within a religious group. But even they tend to become religious groups over time, especially when they become popular. We see this with all of the major religions, including Buddhism.

My teacher, Urgyen Sangharakshita, talking of the Triratna Buddhist Order that he founded, said that it

aims to be a free association of individuals working towards a common goal. It is founded on the principle that spiritual community can be created only by free will and mutual aspiration, never by coercion.4

Notice that he said the Order aims to be a free association of individuals, not that it necessarily is one. At least not all the time in every place. Members of the Order aspire to become individuals, and they will be at different points in that trajectory. There will be some whose individuality is firmly established, while others struggle to achieve this. The latter will oscillate between nascent individuality and a deeply embedded tribal consciousness, which means that they will sometimes experience the Order as a free association of individuals, and at other times as a group. This can occur collectively too. If a few Order members lapse from individual awareness, they not only experience the Order as a group, they turn it into one — a positive group no doubt, but a group nonetheless.

Since the Axial Age there have been many spiritual communities in many different parts of the world. Just to choose one example, the ancient Greek philosophical schools were in fact spiritual communities, as Pierre Hadot makes clear in his book Philosophy as a Way of Life. Hadot was not only an eminent scholar of Greek and Roman philosophy, he was also a practising Stoic. In the book he distinguishes between philosophy as discourse, and as a way of life. The former consists of the ideas and teachings of any particular school, and the latter refers to the ways that the members of that school tried to live and experience those teachings. As he writes, ‘Theory is never an end in itself; it is clearly and decidedly put in the service of practice. Epicurus is explicit on this point: the goal of the science of nature is to obtain the soul’s serenity’.5And they did so together, as a community:

In Epicurean communities, friendship also had its spiritual exercises, carried out in a joyous, relaxed atmosphere. These include the public confession of one’s faults, mutual correction, carried out in a fraternal spirit; and determining one’s conscience. Above all, friendship itself was, as it were, the spiritual exercise par excellence: “each person was to tend towards creating the atmosphere in which hearts could flourish. The main goal was to be happy, and mutual affection and the confidence with which they relied upon each other contributed more than anything else to this happiness”.6

The spiritual community and the group – the effect they have on each other

You may be thinking that the above description of a spiritual community (in this case an Epicurean one) sounds really good for the members of it, but perhaps it’s a little self-indulgent. After all, there are big and urgent world problems needing to be addressed. Shouldn’t we be doing something about them, rather than ‘gazing at our navels’ as the old cliché has it? Sangharakshita had an interesting answer to this question. He said that we need a much bigger perspective on world problems than that which is usually adopted, and proposed the following. Since the Axial Age there has been an ongoing battle between the spiritual community and the group: a non-violent battle on the part of the spiritual community, but not always on the part of the group. Just to remind you of the main differences between them, the group tries to produce good group members, while the spiritual community tries to produce individuals. And the group is based on power, whereas the spiritual community is based on metta — loving kindness or benevolence.

However, although they’re trying to do very different things, they are closely connected, and each influences the other. The spiritual community has, Sangharakshita believed, a refining, softening, and civilising influence on the group, while the group tries to turn the spiritual community into another group, or perhaps tries to annex the spiritual community into itself, which it often succeeds in doing.

Sangharakshita also made the point that all societal and world problems are essentially group problems, which can’t be solved on the level of the group – ‘all that can be achieved is a precarious balance of power between conflicting interests’. He was of the opinion that ultimately there is only one real solution, and it’s a very long-term one:

We need more and more spiritual communities — eventually they should outweigh the group; then there will be an even greater change in the world than that which took place in the Axial Age. The world will be transformed.7

While I think he’s right about the spiritual community having a positive effect on the group (and I’ll give an example below), I have to say that I doubt very much that spiritual communities will one day outweigh the group. If that were the case, we’d expect to see some progress since the Axial Age, and I don’t see any evidence for that. But, to repeat, I do think that spiritual communities can and do have a positive effect on the societies in which they exist. And I believe that leading the spiritual life and forming spiritual communities (not religious groups), is the best way to change the world for the better, in the long run.

How a small but influential group is changing a spiritual community (for the worse)

Spiritual communities face various threats to their existence, depending on which part of the world they’re in. Some countries are governed by totalitarian regimes – communist, fascist, or religious – and the threats to spiritual communities in such countries will be great. If they are lucky the regime will allow them to continue to exist, under certain conditions, or the members of the spiritual community may have to meet in secret, knowing that if they are discovered the penalties would be very severe.

The threat to spiritual communities in free democratic countries is ‘softer’ but more insidious. The biggest threat to the spiritual community of which I’m a member is a phenomenon called Identity Politics. Its advocates conceive of society as essentially made up of groups: male, female, non-binary, straight, gay, bisexual, black, brown, white, Muslim, Christian, Jewish etc – rather than as individual persons who just happen to be male, female, black, white, etc. In fact it should really be called Group Identity Politics. These groups are divided into those that are considered to be ‘oppressors’ and those that are ‘oppressed’, and the purpose of Identity Politics is to gain more power for the oppressed groups.

This is of course a laudable aim, because some groups have historically been oppressed by other groups, or a group. The problem with Identity Politics is not that it promotes the causes of those groups, but that it considers group identity to be the most important thing about the people in them. Notice that all the groups I’ve mentioned – the main ones that Identity Politics is concerned with – are, for the most part, groups that people haven’t chosen to belong to; they were born into them. I include religious groups in this category because Identity Politics is only concerned with those groups whose religion is an aspect of their ethnic background, and so a necessary part of their culture.

Karl Jaspers showed that the great figures of the Axial Age freed themselves from group, or tribal, consciousness and became individuals, and in doing so their empathy – their sense of kinship – radically expanded from their group to the whole human race, and beyond.8 Identity Politics then, is a step backwards, from individual to tribal identity, and from seeing humanity as one related whole – one race – to seeing it as made up of competing tribes. The way to end oppression and inequality is not, I believe, to see people as belonging to groups, whose members all think and behave alike (or should do, according to identitarians) but to see them as human beings, members of the human race.

Identity Politics has made significant inroads into the spiritual community to which I belong, as I believe it has in other spiritual communities in the West, or perhaps I should say the Anglosphere. If we continue to let it do so, then our spiritual community will degenerate into a kind of quasi-Buddhist group, consisting not of individuals, or people trying to become individuals, but of various identity groups or tribes.

How a small spiritual community helped to change a large and powerful group

In his remarkable book Walking with the Wind: a Memoir, John Lewis writes about the Civil Rights Movement in America. In particular, he writes about the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), of which he was a member and leader for many years. Reading this book it became clear to me that the SNCC was a spiritual community, a Christian one, which engaged in a ‘battle’ with a very powerful group — the American government in particular, and white Americans in general.

The Civil Rights Movement differed significantly from Identity Politics in that its aim was for blacks to be seen, treated, and valued as human beings, regardless of colour.

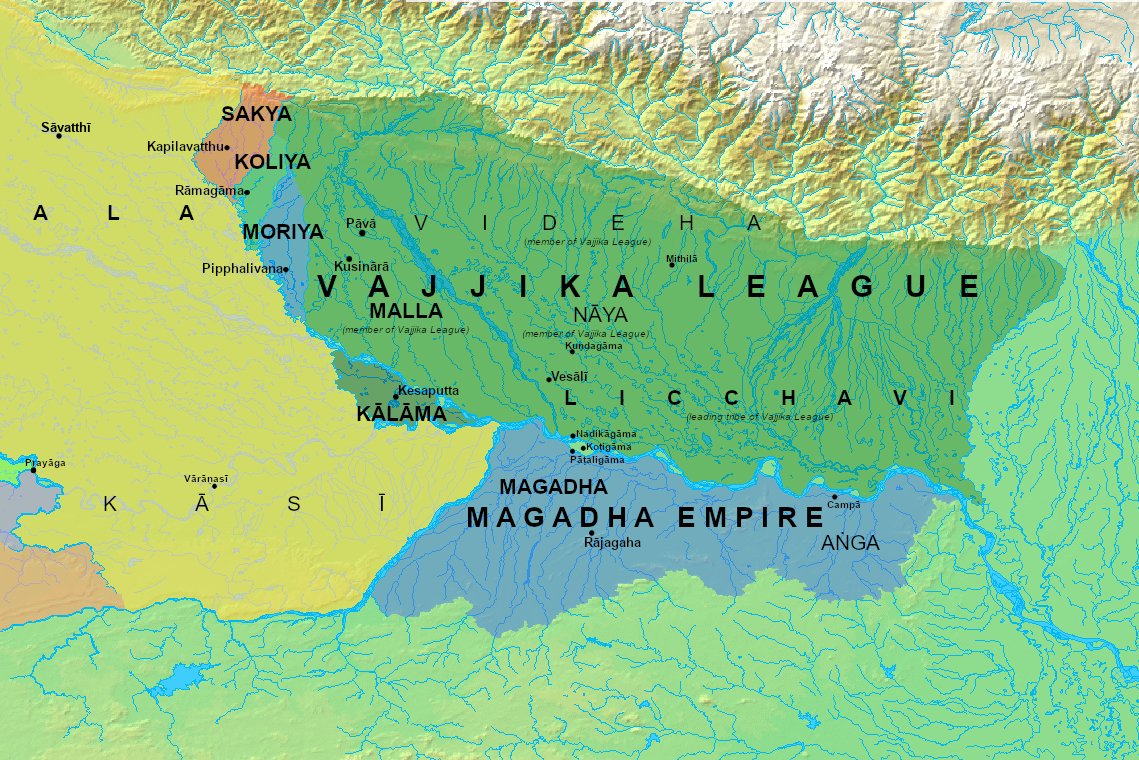

Lewis was 11 years younger than Martin Luther King, whom he revered, and who was the leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Lewis was one of the ‘big six’ leaders of groups who organised the 1963 March on Washington, and two years later he led the first of three Selma-to-Montgomery Marches. This came to be known as Bloody Sunday, because Alabama state troopers, policemen and white bystanders viciously attacked the marchers as they filed off the Edmund Pettus Bridge. (The photo that tops this article is a scene from that attack. It’s likely that the man in the white raincoat is John Lewis.)9

Everyone involved in the SNCC was Christian, and they were, for the most part, committed, practising Christians. They specifically practised non-violence, of which Lewis writes at the beginning of the book:

That path involves nothing less than the pursuit of the most precious and pure concepts I have ever known, an ideal I discovered as a young man that has guided me like a beacon ever since, a concept called the Beloved Community.

Later in the book he explains what these two words mean to him: ‘”Beloved” — not hateful, not violent, not uncaring, not unkind. And “Community” — not separated, not polarised, not adversarial.’

The SNCC’s teacher and trainer in non-violence was a man named Jim Lawson,10and Lewis describes how Lawson used to stage ‘little sociodramas’, in which they all took turns in playing the demonstrators and the antagonists. For instance, they would play out the drama of a ‘sit-in’ at a cafe or restaurant in which blacks were not allowed. Some of them would play themselves while others would act out the white waitresses or angry bystanders, ‘calling us niggers, cursing in our faces, pushing and shoving us to the floor’. Lawson said that simply enduring a beating without retaliating was not enough:

“That urge can’t be there,” he would tell us. “You have to do more than just not hit back. You have to have no desire to hit back. You have to love the person who is hitting you. You’re going to love him.”

And he would stress that non-violence isn’t a technique or a tool to be pulled out when needed, or like a tap you turn on and off, but is something you have to carry inside yourself every minute of the day. You have to be non-violent. Martin Luther King’s organization, the SCLC, also practised non-violence, and Lewis recalls that King used to say ‘you have to love the hell out of them’.

This put me in mind of something the Buddha once said to some of his disciples. Even if a gang of thugs were to use a two-handed saw to cut off your limbs, you should not allow your mind to be adversely affected, but should feel compassionate towards them, radiating loving kindness, with no inner (or secret) hatred towards them. He went on to say that if you were unable to do that, you would not be practising his teaching. The members of the SNCC actually trained themselves to do that in situations of real violence; many of them were maimed, suffered brain damage or were killed.

Lewis also writes about what he calls The Spirit of History, which he says is ‘the essence of the moral force of the universe’, to which we have to surrender. He writes:

To me, that concept of surrender, of giving yourself over to something inexorable, something so much larger than yourself, is the basis of what we call faith. And it is the first and most crucial step toward opening yourself to the Spirit of History…

This opening of the self, this alignment with fate, has nothing to do with ego or self-gratification. On the contrary, it’s an absolutely selfless thing. If the self is involved, the process is interrupted. Something is in the way. The self, even a sense of the self, must be totally removed in order to allow this spirit in. It is a process of giving over one’s very being to whatever role history chooses for you.

Buddhists of a certain kind will perhaps recognise this Spirit of History as something variously called the Bodhicitta, Other-power, or Dharma-Niyama.11They will also recognise the act of a giving up of the self in order to allow the Bodhicitta, or whatever you prefer to call it, to guide you.

One incident that Lewis describes supports Sangharakshita’s belief that a spiritual community has, or can have, a positive effect on a group. In this case it was one very powerful group member, Bobby Kennedy, the United States Attorney General. Lewis describes how he and two members of other civil rights groups had a meeting with Kennedy, who had broken promises or dragged his feet on changes he had said he would make. Lewis writes:

The moment I recall most about that meeting was during a break in the discussions. There was a television on in another room, and it was broadcasting the Floyd Patterson – Sonny Liston heavyweight fight. Bobby Kennedy invited us to come with him and see how it was going. As we stood there, he took me aside and said something I will never forget, an astounding statement, really.

“John,” he said, “the people, the young people of SNCC, have educated me, you have changed me, now I understand.”

That was something to hear, coming from the man who had been reviled by so many of us — including me — for his foot dragging in response to our needs in the South. That showed me something about Bobby Kennedy that I came to respect enormously — the fact that, though he certainly could be stern, firm, even ruthless in some people’s opinion, he was willing to listen, and learn, and change. The same Bobbie Kennedy who had resisted responding to so many of our pleas early on in the movement wound up out front later on, leading a one-man crusade across the country, speaking out against hunger, against poverty, going into Mississippi, into the Southwest, going to the Indian reservations, going into the coalmining sections of West Virginia, standing up and speaking out for the dispossessed of all races – Blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, Appalachian whites. The man really grew. You could see him growing.12

That was the conversion of one powerful man of course, who therefore potentially had a very big influence. But many ordinary citizens were also changed as a result of the work of the SNCC and the other Civil Rights groups of that time.

The black author Shelby Steele said in a recent interview that ‘this country, despite its sins, was also a country that, for the last sixty years, has truly transformed itself — morally. And Americans today are different people in regard to all these issues.’13

Steele was a boy at the time of the Civil Rights era, and in another interview he recounted an incident in which his family were having a picnic in a park. A white man approached and punched Steele’s father in the face. His father didn’t retaliate, but just continued to stand in front of his attacker looking him in the eyes. After a few moments his assailant, ‘mortified’ according to Steele, apologised for what he’d done.14

It seems that at that moment the white man’s consciousness changed. Before that he had seen Steele’s father only as a member of a group, the black group that he despised. But as he (Steele’s father) looked him in the eye he saw a human being, a fellow member of the human race, and he was suddenly ashamed of his behaviour.

This probably wouldn’t have happened if a gang of white men had attacked him. It’s easier to commit an act of violence when other members of your tribe are doing so. His lone attacker in that case would not have been able to stop and apologise in such a circumstance. Even if he had felt the wrongness of what he was doing, he would surely have suppressed it, because he would know that the other member of the gang would have turned upon him too. He would, in their eyes, have been a traitor.

This is the only ‘weapon’ members of the spiritual community have. Their dignified, courageous willingness to meet violence with non-violence. To meet hatred with love. They invite their attackers to step out of group consciousness into individual consciousness, to become fully human. This is what spiritual communities, or perhaps I should say individual members of spiritual communities, offer to the world. It may not be enough to prevent Nuclear Armageddon, but it’s the only chance we have.

Footnotes

- Parker J Palmer, The Courage to Teach, page 90.

- A state of serene calmness.

- Karl Jaspers. The Origin and Goal of History, Ch.1, The Axial Period.

- https://thebuddhistcentre.com/text/order-members

- Philosophy as a Way of Life, Pierre Hadot. P. 60.

- Ibid, pages 88 to 89. The quotation in this passage is from Epicure by André-Jean Festugière.

- A Vision of History. https://www.freebuddhistaudio.com/texts/read?num=136&at=text&q=&p=5

- In the case of the Buddha, for instance, it included all non-human beings too.

- Courtesy of Civil Rights Movement Archive

- Interestingly, Lawson studied with them the Axial Age Chinese thinkers Mo-tzu and Lao Tzu, amongst others.

- Buddhists of another kind will not recognize this at all, and will say that the idea of such a ‘force’ has no place in Buddhism.

- As we know, some years later, as he was running for Presidency, he was assassinated.

- Shelby Steele On “How America’s Past Sins Have Polarized Our Country” – YouTube. 3.20.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b-Dw8JRYkpI&t=683s (from 10.10)